Andrew Shirman (石安祝), originally from the US, is the CEO and co-founder of Education in Sight, a nonprofit that provides access to eye exams and eyeglasses for underprivileged children in Western China. He is also the co-founder of Mantra, a sunglasses company and social enterprise that donates a pair of eyeglasses to a child in need for every pair of sunglasses it sells. This interview was conducted by CDB’s Gabriel Corsetti and Zou Yun, and took place in Beijing on January 10, 2018.

CDB: Could you please tell CDB’s readers a bit about how you created Education in Sight and Mantra?

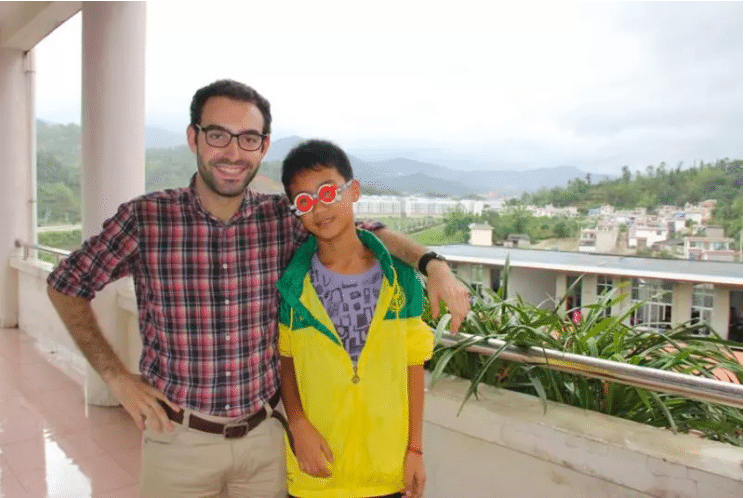

Andrew Shirman: It was in the fall of 2010, when I joined an organization called Teach for China to do volunteer teaching in Yunnan for two years. I was a seventh grade teacher, I had a class of 47 students, and every single day I was in there teaching them English, getting them ready for their Zhongkao (中考, middle school exam) and working with them. Our school had really low resources, it was way way out in the middle of nowhere. From Beijing, it would’ve been a three and a half hour plane ride to Kunming and then a nine hour bus ride to Fengqing (凤庆), where the school was. I got to see just how much my students struggled because they were coming from the countryside.

The thing that surprised me the most was that so many of the kids in my school were near-sighted. I could see them squinting, trying to copy notes from the person next to them, but none of them had the eyeglasses that they needed. After my first year seeing how that affected my kids, and seeing some of my best students drop out because they never got the eyeglasses they needed, I decided to start a simple project that brought eye doctors directly to my school, gave eye exams to all the students and then delivered eyeglasses.

So long story short, we saw the success of the program and we decided to turn it into something more than just a teacher-project. We started to raise money, institutionalize our resources and build what would become Education in Sight. So after quitting my job in Boston, I moved back to China and started to do Education in Sight full time. We were still really small, it was just me and Sam, my co-founder in Mantra, who was another guy I taught with in the countryside and one of my best friends there.

It was just the two of us figuring out how to make Education in Sight work, and we had a donor whose corporation was in Sichuan that wanted to partner with us. They were interested in doing something good but they also wanted to market it, because they were a concert company, and they wanted to show videos of their charity work before their concerts. So they promised a donation of 50,000 dollars. They gave us a couple thousand dollars upfront so that we could do a project in a few schools and they took a bunch of films of it, then came to our schools in Yunnan and got all the material.

At that point there were two months before the next semester, when we going to launch the rest of our project that we had partnered with them on. And two months passed, we submitted all the budgets, everything looked good, and we started sending them message after message saying “hey, when could we expect the transfer? We’ve started work, and everything’s looking good, we are ready to go.” They kept saying “next week, next week, we’re just waiting for final approval”, and then at some point we said “hey, we need this money by next Tuesday, this is the deadline for us, we need it by then”. Tuesday came and our liaison there sent us a text message saying ‘Hey, we don’t want to work with Education in Sight any more. Good luck in the future.’ And all of a sudden we were in a mess, because we had already started all of our programming, and they had taken everything they needed from us for marketing and now they weren’t delivering on their promise.

And so we had to scramble to make sure our program survived. We found friends where we didn’t know that we had them. We got through it, but Sam and I looked at each other and decided we wanted to find a way to make Education in Sight more financially sustainable. We started looking for social enterprise models and it was at that time that we realized we had a huge opportunity, because we didn’t see anything like that in China. We knew that it had been widely successful in the US. We also knew, based on our conversation with Chinese consumers and friends, that there was a demand for something like this for socially responsible consumers.

CDB: So in this area of Yunnan where you were teaching a lot of children didn’t have eyeglasses even though they needed them. Was it mainly because their families didn’t have enough money to buy them eyeglasses, or was it is because they didn’t realize it was necessary, and the children themselves were not asked?

AS: Well we started our project in 2012, and went full time on it in 2014, and over the years we have gotten some pretty good data. It’s a complex problem, but it really boils down to about three things. The first problem, and actually the smallest one, is affordability. Glasses are still a few hundred RMB even in the countryside, and in the areas where we work, where families suffer from poverty, extreme poverty, a few hundred RMB represents a lot of money. And so obviously, not everybody’s going to go out and buy the glasses. But the other two problems we found were actually larger ones, and if you solve those people find the money for the glasses that they need.

The first one is access. So you are in the countryside, in the mountains, the nearest eye doctor may be five or six hours away by bus, and if you are student, you are at your school most of the time, your parents are somewhere else, and the eye center is in a third location. It’s really difficult to coordinate all those pieces together, and so getting actual eye exams is almost impossible (if there even is an oculist around, for that matter). And then the third issue, tied into all these things and underlying them, is awareness and behavior. We have found that people aren’t drawing the connection that if the kids can’t see in class, the problem is near sightedness, and it’s going to affect their long-term ability to study in school. And people who are aware of eye glasses often times think that they are harmful for students’ eyes, that if you give a kid a pair of glasses it will make their nearsightedness worse, it will never fix itself, and it will become a problem.

CDB: Are you referring mainly to the teachers or the parents here?

AS: Teachers and parents both think that. So our program works to solve access by bringing eye doctors directly to schools and to solve affordability by giving out free eyeglasses, and then on top of that we do educational work. We educate volunteers in every school, so they can then educate all the 班主任 (class heads) and all the students in the school about why glasses are important, how much it can affect your future and your grades, and then what good behavior is: going to get eye exams every year, telling your teachers and parents if you can’t see clearly in class. This way we create a chain that solves these problem even if we’re not always running a project there.

CDB: So raising awareness is crucial.

AS: It’s the hardest part for us, awareness-raising is such a difficult thing to do compared to just giving something. But that’s a major priority for us in 2018 actually. We have become really good at delivering glasses, that whole pillar of our program is top notch. You could say that pillar is just about done, it’s about 90% complete compared to where we want it to be. Now we are looking at our awareness/behavior change pillar. This is probably about 50% of the way there. We have basic materials and we’ve seen good outcomes, but we are not seeing 80%, 90% positive outcomes. So we are going back and revitalizing all of our education training curriculum, our pedagogy, and we are planning to launch that by the end of this year.

It’s about training the trainers. Since we’ve started, we’ve worked in over 400 schools, we’ve given out over 170,000 eye exams, and delivered over 25,000 pairs of eye glasses. And the way we’ve been able to do all that is that we do very small amounts of work ourselves in all of these schools. What we actually do is train site leaders, who are local teachers or school nurse volunteers, to help us coordinate the project. We manage these large groups through WeChat, since people in the countryside do have smartphones thank god, and we coordinate with them and coordinate with local hospitals to make sure all of these pieces are in play.

CDB: Is Education in Sight officially registered as a non-profit in China?

AS: We partner with Chinese foundations. We are in the process of registering our own local charity in Yunnan, but meanwhile we partner with organizations like the China Children and Teenagers Foundation and the Asia Academy of Philanthropy, and it’s through them and their connections, and honestly their generosity, that we’ve been able to run our programs in China. The goal for China is this: even though I am a foreigner, and I was the person who started things up, I don’t want to get in the way of Education in Sight’s growth, so everything in the future is building towards it becoming a wholly Chinese-owned organization. I think if you are going to do meaningful, impactful, and long-term charity work in China, the best people to lead are Chinese people. They will have a better understanding than I ever will.

CDB: So after starting a non-profit you created a social enterprise, because you felt it would be more financially sustainable. What do you think the advantages and disadvantages are of the two different forms of organizations, non-profit and social enterprise, in terms of helping your target group? Do you think there are advantages in just being a pure non-profit?

AS: So we started Education in Sight, which was a total charity, but after that incident happened, we started to think about social enterprise models. And through sheer stubbornness, Sam and I decided that we wanted to start China’s first “buy one donate one” eyeware company. Are you familiar with ‘Toms shoes’? They started off between Argentina and the US in 2006. They make these very simple 布鞋 (cloth shoes), and for every pair of ‘Toms Shoes’ you buy, they donate a pair to somebody in the developing world that needs a new pair of shoes. It started in 2006, and now it’s a billion-dollar company.

We were looking in China, and we knew that Chinese consumers really wanted to find a more socially conscious way of consuming, and that there was nothing like that yet. Still in a large part there isn’t. So we decided to create a lifestyle brand with unique designs inspired by where we’ve worked with the social mission. And that’s what Mantra is. It’s a successful for-profit business, we’ve raised investment for it, we have had thousands of sales and tens of thousands of WeChat followers, and we’re trying to grow.

There are tons of both advantages and disadvantages. So to give you a view from behind the scenes of how all this works: we operate these two independent organizations because we have two independent visions of what we are building towards, and there are always fundamental differences of vision between a for-profit and a non-profit. I lead Education in Sight, and maintain founder status. I’m a co-founder of Mantra, but Sam, my fellow co-founder, is the CEO and leader of Mantra. So we are in the same office, we have the same conversations, we plan together but we divide our concrete responsibilities, and so neither one of us is torn apart by the need to be giving while at the same time trying to sell as many glasses as possible. If there was only one of us I don’t know if we could do it, but I trust Sam more than anyone in the world and we have worked together for over a half of decade. It’s because of our partnership that we’ve been able to go so far.

CDB: Do you feel that the concept of social enterprise, or shehuiqiye (社会企业), has a good recognition in China?

AS: It certainly has a way bigger awareness than it did two or three years ago. When Sam and I started building Mantra and pitching to people, we would pitch to anybody just to practice. I’d say 90% of the Chinese people we talked to had never heard of the term ‘shehuiqiye’ before. These were young, well-educated Chinese in the Mainland. Part of it is that now we have built a following and we are having a lot more conversations with them, but also just in general I think social enterprises are really starting to blossom.

It seems like something that’s starting to take off in cities first, just in terms of awareness around international trends and things like that. I don’t think it’s something you hear thrown around in counties in rural China or anything like that, but there are a lot of social enterprises emerging from these counties, for instance some Teach for China Fellows, who taught for two years, saw a need and now they are selling local consumers goods to support families so that they don’t have to go and 打工 (do manual labour), and they can stay in their county. There is a ton of awesome creative stuff coming out of China right now.

CDB: It is very difficult to run an NGO in China, even in the case of domestic organizations, so I was wondering what it feels like to launch an NGO as a foreigner.

AS: It’s exhausting. It’s difficult. The first few years were really tough. I mean, compared to building an NGO in the US or Europe or a lot of other places, you are just at a handicap for everything. There are fewer large donors in China, or should I say, there are fewer institutional donors that will help you grow your organization. For me, personally, language is always a barrier. I can speak Chinese but not perfect Chinese, although enough to work with my team. And then you are working through a very complex registration system as well, and so there are a lot of barriers at every step of the way. One of the biggest challenges, at least from the Education in Sight side of things, has been trying to grow the organization from an administrative perspective. We’ve had a lot of people who want to donate glasses and want to donate money that goes to getting kids glasses, but in the same breath they’ll say “but it cannot go to support the team”. Because of all of the scandals and the trust that’s been hurt overtime in China, it’s really difficult to raise money for team salaries to expand our organization, the way we need to in order to continue growing overall.

But that being said there have also been some things about China that have really worked well and are really exciting. We’ve been able to develop good relationships with our local government partners, and they have opened the door to us working in their counties. We’ve been able to create agreements with them because they see the need, they see the possibility as well as what their county would look like if their kids got glasses, and they’ll invite every principal of every school in every county for us to introduce the program, they’ll get us connected to the local health department and the local hospital and help us negotiate how we are going to be able to use hospital time to get kids eye exams. Anyway, that’s how we have been able to work in four hundred schools, with the institutional support of our county and prefecture-level partners.

By and large, people have been very positive. Actually we’ve just fielded surveys gathering attitudes and behaviors from our teachers and our students about how successful our program has been one year after we ran it. We went back to the communities where we ran it a year ago and fielded self-report surveys. There was very positive feedback about the difference teachers and students have seen in the classroom. 83% of the teachers agreed with the statement that they would recommend Education in Sight projects to another school, and 90% of primary school teachers agreed with it. And then we had about 90% satisfaction with our schools, so we are pretty pleased with those numbers. We consider that a big success, because it is difficult to make everybody happy. 90% is pretty good. We’d love to make it 95% but still, good reception. We’ve also seen that it made a real difference with attitudes. We don’t have baseline data, but what we do have is the figure for what percentage of teachers agree with the statement that eyeglasses have a positive effect on children’s academics, and whether or not they encourage students to wear glasses in the classroom. And those numbers are anywhere from 70% to 85%, which is also pretty good.

CDB: You said running an NGO in China is exhausting, but you don’t give up. What keeps you going?

AS: I got to be a teacher in the countryside for two years and I had my kids, and I got to see them succeed and to see them fail, and it changed my life. Before that, I was just a kid coming from the mid-west of the US and I hadn’t seen too much of what the world had to offer. I really cared about my students’ success, I really felt responsible for my classroom and how what I was doing was going to affect their future, and for anybody who’s been a teacher, there is really nothing more incredible than seeing a student struggling ultimately succeed and knowing that you played a part in that. I think that every piece of work I do in Education in Sight gets to reinforce that. The data is in on this, nothing is more effective than giving a kid a pair of eyeglasses if they are nearsighted. The way it affects a kid’s behavior, their test scores and their future is unbelievable. Five times more effective than anything else you could do in the countryside. And so I have a real conviction that the work we do is important and I love doing it.

CDB: What are your plans for the future? Have you considered expanding your program nationwide, or do you maybe feel like focusing only on eyeglasses is not enough?

AS: So we have plans for the future, big plans. I will speak about Mantra first. Mantra is gearing up for a big 2018. It’s going to be “make or break” for us. In the past we only sold sunglasses, but we have just launched our optical line, so we sell regular eyeglasses through our platform now. We’re working at new designs, better designs, rebranding and creating an experience that really brings our customers into the social mission. We’ve been able to do that alright so far, but we really want to stand out with that in 2018, and then use that as a platform for continuing to grow. So I think that’s what you will see for Mantra in 2018. For Education in Sight, we have the eyeglasses delivery part down, so how do we improve awareness? In the past, we really focused on working in every single school in the county, solving the problems for all of the students that were there for those two or three years that we were working in that county, and we did not do enough thinking about what happens a year later, three years later, five years later.

So a lot of this past year for us was about refreshing our strategy, and making the program that we do now only the first part of Education in Sight, creating systems, programs, procedures for handing off a project to a county, so that over time they are relying on us less and less but continuing to have the same output for students by still doing regular eye exams in schools, having subsidized glasses for kids who are under the poverty line, and conducting continued awareness campaigns. So we are going be working on rolling that out in 2018.

Coming to your question on what’s our plan to expand, right now we are focused on Yunnan, and on really getting all of our programing elements right, so we can essentially turn it into a package. What I’d love to do is to have a manual, and a procedure, and a plan for how anybody can run an Education in Sight project. Then in the future we can work with other local NGO partners in Sichuan or Qinghai or wherever, and train them to run the projects and help them get certain resources, but then they can also leverage their own local resources to run the projects themselves. And I think that it would be a really great outcome for us. If I’m speaking honestly we are not going to be the people that solve this problem in China, the country’s too big, and we just can’t do it alone. But we can find partners, larger foundations, government institutions that can solve the problem for themselves at a local, county, prefecture, and even potentially province level. We’d love to be supporting these efforts.

CDB: Have you considered whether this model would work in other developing countries?

AS: We haven’t thought about it too much. China’s enough for the moment (laughs). We’ve given out 25,000 pairs of glasses, and for some countries, that would literally solve the problem. For us it only puts a small dent into Yunnan Province. And so we could spend the rest of our lives just trying to get China right, and we haven’t had ambitions yet to expand outwards to other countries, though the need is definitely there.

CDB: What’s your personal career plan? Are you going to stay in China the rest of your life to get things right?

AS: Overtime, my goal would be to make Education in Sight a fully Chinese institution. I’d like to find a strong leadership team and long-term supporters, and then work to continue giving support, but in an advisory role.

CDB: Is there anything that happened in these past five years that hit you the most? Any particular anecdotes you would like to share with us?

AS: Well, when you talk to the kids, it’s difficult because they are really shy. But when you start to ask them questions about their life, where they are coming from, what their whole world, with or without a clear vision, it’s all incredible. Maybe the most touching story for me is from when we working in Longling county, almost two years ago. There was this girl there who was a sixth grade student, her English name was Sally. She was a great kid, a good student in the classroom. When she grew up she wanted to be a teacher or doctor, she wanted to help people. But even as a sixth-grader, she had had the most incredibly difficult life: when she was really young her father died of a disease, and her mom remarried another man and left town, and put her in the care of her aunt, who never planned to take care of Sally, ever.

So she knew what a responsibility she was putting on her aunt, and she knew exactly what was happening in her life even though she was so young. She worked really hard in school, but around the end of the fifth grade and the beginning of sixth grade she started to not be able to see clearly anymore, and she knew that her eyes were starting to have this problem. She panicked because she was too afraid to ask her aunt, who’d already taken on this incredible负担 (burden) to take care of her, to buy glasses. She didn’t want to do it. She was just going to suck it up and keep trying to work as hard as she could, even though her eyes were disappearing day after day, and they were only going to get worse in middle school.

That year was the year we came to her school, and brought in the eye doctors, gave the eye exams, and got Sally the glasses that she needed, and now she’s in seventh grade. She’s killing it. And it potentially completely changed the trajectory that she was on. It scares me to think about what would have happened if she hadn’t got the glasses that she needed. It’s still that way for 30 million kids across China.