This article is part of CDB’s Special Focus on ‘Effective Communication and Cooperation between NGOs and Business’. It originally formed the sixth case study in CDB’s latest research report which we released in July 2015 (you can view the original here). Over the next few weeks we will be publishing translations of the ten case studies contained in that report. The case studies detail partnerships between Chinese NGOs, foundations, and businesses.

Editor’s Note: The first half of this article discusses NGO-CSR relations. The CreditEase case study can be found halfway down.

Businesses often interpret “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) differently. Businesses also require of their NGO partners a multitude of goals. What type of business can develop to become an important partner for NGOs?

Finding the right CSR partner

There are various ways of categorizing businesses. For example, in terms of the size, businesses can be categorized as large, medium-sized companies, and small businesses. In terms of the ownership structure, there are domestic private ownership, state ownership, foreign ownership, diversified ownership and so on. Furthermore, different sectors and industries, for instance, manufacturing, energy, IT and financial industry, will have different focus areas for CSR. Other factors, such as local culture and beliefs, objectively contribute to the formation of businesses’ cultural gene as well. NGOs have to identify and determine their potential partners. They also need to understand and answer the following questions: what are the characteristics of corporate-NGO partnerships and requirements demanded by different sectors and types of businesses at different stages of development? At what levels can public interest NGOs and corporations reach a consensus and seek cooperation? How can these two pool efforts to promote corporate-NGO partnerships beyond the limitation imposed by the concept of “resources input/output”, in order to become effective contributors in society together?

A diagram prepared by CSR expert Fu Lin (originally published in China Development Brief 2013 Summer Volume) analyzes CSR requirements and performances of businesses at different stages of development. Fu divides businesses’ stages of development into 1) start-up/growth stage aiming at existence and survival, 2) maturity stage at which the business has become more comprehensive and systematic and finally 3) transition stage. This can help public interest NGOs to better analyze businesses. All businesses will go through the inception, start-up, growth, and mature stages as they develop. They will create greater values, become more rational, and improve their performance. As mentioned before, businesses at different stages of development will often have different approaches to CSR.

It is important for public interest NGOs to pay attention to a business’ stage of development. Multinational corporations are usually at the mature stage while most of the domestic Chinese businesses are at the growth stage. Concerning CSR investment, businesses at the mature stage tend to make more substantial investments in CSR, due to the maturity and stability of their markets. International companies usually give their preference to crucial global issues, often associated with goals such as the UN’s MDG’s (Millennium Development Goals), international human rights standards, and climate change agreements. Obviously, obtaining the Chinese government’s approval and recognition is still the biggest task for them in China. Thus, they are concerned with integration into the community and their employee volunteer program.

When survival is no longer a struggle for the business, greater emphasis will be placed on its long-term development. International companies at the mature stage have their own unique strategies. Business have different strategies to meet the localization requirements for the Chinese market. For some companies, the headquarters designate the CSR issues or areas vertically to their subsidiaries or branch offices, but they will not lay down specific requirements on which NGO partners to choose. For others, the CSR Departments are relatively more independent due to the large scale of the Chinese market. Chinese subsidiaries can freely decide and choose which CSR issues to tackle. Some topics on local issues in China will also be considered. How businesses choose their NGO partners highly depends on their annual strategies. For instance, the company might focus on environmental issues in one quarter but emphasize educational issues in the next quarter. Yet, this does not mean that the company’s CSR projects do not follow a pattern. Once the company chooses the CSR area that it will focus on, the life cycle of its CSR focus area is not calculated or determined on the quarterly basis. Instead, in general businesses need a degree of continuity. When doing annual strategic planning, businesses only make some slight changes for those mature projects at the implementation level and seldom reshuffle them. Otherwise, this would increase the operating costs and cause inefficiency to both the owners and employees.

The culture, competitiveness and product positioning of the business will also affect the choice of its CSR focus area. Take Intel as an example. When it decides on its CSR projects, it might select those related to its core competencies, such as education, innovation or high-technology. If a cosmetics company in China targets women, it might take on the mission of enhancing the well-being of women. For this company the All China Women’s Federation might be the preferred partner if they have little knowledge of grassroots women’s organizations. Businesses in different industries might also be concerned about gender or children’s issues. For example, an investment company might be concerned with women entrepreneurs, or a nutritional company might work on child health issues. Moreover, the CSR department of some businesses might be responsible for cause marketing, like promoting a product within a specific period of time for public welfare. The sales income then might be used for executing public interest projects by selecting and collaborating with selected local partners.

When NGOs try to match themselves with big international companies and look for shared core values, experts suggest that they can check UN’s Millennium Development Goals Report and other important global issues, which big international companies should be concerned about. Moreover, each company will provide information on areas related to CSR strategy and CSR investment on their own website. For Chinese companies, there might be a close linkage between their CSR activities and brand promotion because they are still at an early stage of growth. For most businesses, they usually have top-down decision-making styles for their internal processes. When NGOs need some financial support, the success rate of cooperation with the business is higher if the business’s top management lay emphasis on CSR. Businesses from different countries have different CSR preferences as well. For example, businesses in the UK and Italy value contributions to the community, while France has stricter environmental requirements.

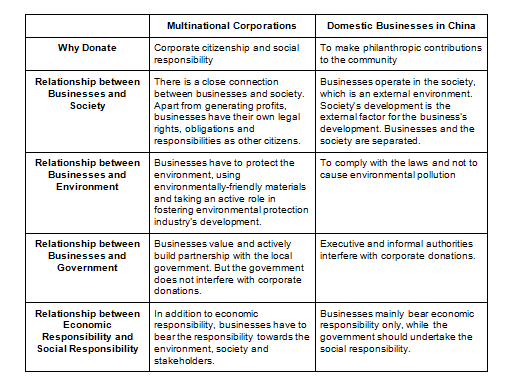

Recently, changes have taken place in the CSR philosophy and practices of Chinese domestic enterprises. In 2007, the Institute of Sociology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) issued a report “A Comparative Study of the Donating Behavior of Multinational Corporations and Chinese Businesses”, comparing the difference between multinational corporations and Chinese domestic enterprises in terms of donation (as shown in the chart below). The differences concerning basic presumption and donation philosophy are as follows:

At the CRO Forum in January 2015, Chen Feng, Head of Research Section 1 of Research Bureau of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) shared the impacts of the government’s efforts in promoting the development of CSR, plus the future directions. In terms of the purpose of corporate donations and relationship between businesses and environment/society, it is noteworthy that Mr. Chen mentioned that the situation now is very different from that in 2007, especially for leading Chinese state-owned enterprises, and large private enterprises such as Huawei. According to the 2007 research report mentioned above, most Chinese companies in 2007 had only a poor understanding of the concept of “social responsibility”. They held the view that economic responsibility was the main responsibility of businesses – including generating profits, paying taxes and providing jobs – and that government should undertake “social responsibility”. Many businesses were still stuck at the most basic level of the CSR Pyramid, perceiving CSR as an economic responsibility only.

However, today, CSR in China covers a wider range of issues, such as anti-discrimination, environmental responsibility, community investment and supply chain management. Some companies have sorted out and modified the terms of their internal systems which are inconsistent with their CSR policies one by one. For instance, the original recruitment system would be modified if it is found to have involved ethnic discrimination, gender discrimination or “hukou-based” discrimination, so as to reduce the company’s operational risks. In the past, local government approval was the only factor considered by big Chinese chemical companies when choosing a site to build their chemical plants. However, these chemical plants are now concerned about the growing number of NIMBY (Not in My Backyard) movements, often against PX projects or the construction of waste incinerators. As a consequence, these chemical plants now have to consider the factors of both financial returns and the reactions of local people in the process of site selection.

Many businesses have either passively or actively integrated the ideas of social responsibility and sustainable development into their strategic decisions. State-owned enterprises also now assume an active role regarding some significant social issues. Some businesses go even further to be members of international CSR networks, with their CSR projects recognized as best CSR practices by some international organizations like the United Nations Global Compact. Huawei’s CSR Department for example is equipped with great power. When Huawei wants to develop or modify a system, it should include its Sustainable Development Department in the decision-making process so that the department can help eliminate the risks found in the system or documents from the perspective of sustainable development and CSR. Concerning the supply chain management, Huawei extended the CSR requirements to all members of the supply chain. Huawei established a “Supplier CSR Committee” chaired by the chief procurement officer, with procurement supervisors and CSR experts being other committee members.

Although state-owned enterprises now place greater emphasis on CSR development, it seems that Chinese NGOs still do not get more opportunities for cooperation with them. As shown by a survey in 2011, NGOs were more likely to partner with large multinational corporations and private enterprises but there was only very limited cooperation between Chinese NGOs and state-owned enterprises. Despite few examples of successful co-operation, there are some Chinese NGOs that have tried to explore opportunities for co-operation with state-owned enterprises. Practitioners think that whether state-owned enterprises choose to cooperate with NGOs depends on two key factors. The first one is to see whether the person-in-charge of the business takes CSR seriously. Another one is whether the doubts and misunderstanding towards NGOs – which have existed for a long time – can be eliminated. State-owned enterprises have doubts about the position, purpose, abilities and strength of NGOs. In general, large state-owned enterprises tend to assign the jobs to government-backed organizations or research institutes, as they think that they are all within the same system and government-backed organizations usually have greater financial strength and good reputation. Of course, multinational corporations are also more willing to form partnerships with government-backed organizations, with the hope of building good business-government relations.

Large state-owned enterprises have taken a leading role in the field of domestic CSR. However, the majority of Chinese business participants of the UN Global Compact are still private enterprises, and there are only 15 state-owned enterprises. Georg Kell, Executive Director of the UN Global Compact, thinks that this is likely due to the global value chain. Private enterprises are in the value chain of multinational corporations, with the incentive and records of solving the environmental and social problems. However, there are only around 300 private enterprise participants, which comprise a very small proportion of private enterprises in China. In terms of investment, taxation, employment and GDP contribution, private enterprises possess an advantage. Despite that, most private enterprises still rely on the government’s mobilization work heavily to do charitable activities like make donations. This is reflected by the fact that nearly all government departments approach businesses for money in the name of “public welfare” or “philanthropy”. The main problem faced by most Chinese private entrepreneurs now is that they cannot distinguish the concepts of “public welfare” and “philanthropy”. They also do not know which aspect they should focus on.

Private enterprises in China are at different stages of CSR. The leading ones have already begun combining their core businesses with CSR. In the case study below, we look at the Beijing-based CreditEase as an example ((http://english.creditease.cn/about/Overview.html)). Compared to many other companies, the scale of its CSR Department is much larger. Its CSR Department can help to facilitate the development of the company’s core businesses internally as well. Not only does this prevent CreditEase’s CSR Department from becoming marginalized and even closed-down during economic downturns, but it can also help to turn the department into the company’s new business “incubator”. CreditEase believes that it is meaningless to do the work if it fails to create real impacts on business development. It applies the same logic to CSR: a CSR project is not worthwhile if it cannot lead to direct strategic changes. There are several benefits of doing this. First, through helping the company to develop its own edge and the staff to develop their own expertise, it can help the company to achieve good social performance with positive effects of CSR projects. Second, it can foster the business growth and development of the company. CreditEase’s CSR Department then provides specific social responsibility projects according to the needs of different customer segments. For example, it offers investor education programmes to inculcate investors with the knowledge of wealth management or even life planning. CreditEase’s corporate volunteer team have local community or school visits to give fraud prevention advice to elderly people as well as teaching kids to manage their Yasuiqian (traditional New Year gift of money to children). For microentrepreneurs, CreditEase provides capacity-building projects. By using a variety of methods such as training programmes offered by high-end business schools, online education courses, professional expertise support, CreditEase can help these microentrepreneurs to strengthen their managerial capacities. Regarding poor rural women, in 2009 CreditEase officially launched its non-profit microfinance project YiNongDai to help them get rid of poverty and become better off. YiNongDai is CreditEase’s first CSR project and first product serving rural markets. Two years later, CreditEase introduced agricultural related services one after another, such as Inclusive Finance Wholesale Fund I, NongShangDai and agricultural machinery leasing service. Additionally, it set up Agricultural Credit Service Department, which has already built a nationwide service network covering over 60 locations and employed more than 1000 staff.

Case study: CreditEase’s YiNongDai CSR project

CreditEase, founded in 2006, is a P2P microcredit platform. By building a credit platform between debtors and creditors, funds are circulated in a targeted manner. Since the inception stage of the business, CreditEase has had a strong public welfare culture. Its founder visited Bangladesh and learned the micro-finance model of the Grameen Bank initiated by Muhammad Yunus. He witnessed firsthand how micro-finance can play a major role in helping farmers shed themselves of poverty. Muhammad Yunus’s core belief that “the poor are creditworthy and credits have value” has become a fundamental pillar of CreditEase’s strategy. Given such a background, CreditEase has had a very clear CSR positioning from the outset, always focusing on “strategic CSR”, meaning that it should be relevant to the strategic development of the company, instead of just focusing on simple short-term expenditure such as monetary donations.

CreditEase’s microfinance business has developed rapidly in urban areas since its establishment, and successfully helped a group of micro entrepreneurs, urban white-collar workers and university students solve their financial problems. In just a few years CreditEase has grown to be the leader of the Chinese P2P industry. At the same time, however, CreditEase found that its business could not benefit the low-income groups in rural areas, while helping this group of people is the main objective of many international micro-finance institutions and the inherent requirement for CreditEase’s corporate culture. Subsequently, this area is now being given attention by CreditEase’s CSR Department. CreditEase discovered that international organizations and national research institutions have already introduced and practiced microfinance in China for many years. Meanwhile, many non-profit Microfinance Institutions also already operate in rural areas. These microfinance institutions offer unsecured microfinance loans to low-income groups in rural areas, hoping to provide opportunities of self-employment and self-development for them through financial services, and foster their self-reliance and development. Nonetheless, these organizations face a developmental problem. Due to a lack of financial strength, these organizations has operated under a “low cost, low interest” model. But still their funds have been inadequate to meet the demand of poor farmers and fundraising has become the biggest problem that Microfinance Institutions need to deal with. CreditEase thus can use its accumulated experience in the P2P field to facilitate social charity funds to flow towards rural areas where there are only limited financial services available. This allows more farmers to gain their desired loans and helps non-profit Microfinance Institutions to acquire more funds.

In 2009, CreditEase established a non-profit online micro-finance service platform called YiNongDai. Its aim is to offer financial services to rural women in impoverished areas. YiNongDai has developed a new set of lending rules. CreditEase first establishes partnerships with non-profit Microfinance Institutions (MFI) in financially challenged areas. These MFIs select farmers who meet YiNongDai’s objectives from their loan applicants. Their village loan officers then conduct credit reviews for these applicants. Once the applicant passes the credit review, the MFIs will give her loan information to YiNongDai platform. Due to the cyclical nature of agricultural production projects like breeding and cultivation on which farmers will spend most of their loans, and the fact that YiNongDai platform’s fundraising takes time, the MFIs will lend money to the eligible farmers with good credit first. Later YiNongDai will put the debtor’s information online, so that supporters can access the information of rural women borrowers on the website, such as their photos, borrowing purpose, desired loan amount, desired loan amount not given, family’s financial situation, etc. The supporters thus can lend their money to these rural women through buying the debts of MFIs which the borrowers belong to. Rural women will repay the loan on time to the MFIs first, and the MFIs will then repay both the principal plus estimated 2% annualized income as thanksgiving to the benevolent lenders via YiNongDai platform. By the above means, YiNongDai conveys the farmers’ information to the society and urban lenders can change their spare funds into charity loans. This can enhance the lending capacity of MFIs to help more poor women.

YiNongDai targets farmers without any collateral. Taking such a huge risk in a CSR project was the most serious challenge that CreditEase’s CSR Department has ever encountered. If the risks cannot be effectively controlled, this would lead to the failure of this CSR project as well as threatening the future development of the company. Hence, CreditEase’s CSR Department has drawn some lessons from the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, using its “Group Lending Model” to control risks. And this approach requires CreditEase to build strong partnerships with non-profit MFIs across the country.

Most of the non-profit MFIs, which work in partnership with CreditEase, are operating as private non-enterprise units or societies like women’s development association, and women support association. The loan officers hired by these organizations usually live in the same community or even same village with the borrowers. Therefore, they are very familiar with the situation of farmers. It can help to ensure the effectiveness of credit reviews by collecting farmers’ information through these loan officers. With the liaising efforts of the loan officers, the borrowers form a co-guarantee group of three to five who are jointly liable for all loans taken out. This helps to ensure YiNongDai platform’s loan security.

At the same time, YiNongDai makes payment and settlement with MFIs each month, so as to determine the debtor-creditor relationship between the borrower and the lender. If the farmer fails to pay on time, these MFIs themselves have to repay the loan according to the agreements. For MFIs, only by safeguarding the lender’s financial security can they get constant support from YiNongDai platform. With the endeavor of the MFIs, YiNongDai platform has maintained a very high repayment rate of 100%, which has basically eliminated the worries of supporters.

XiXiang Women’s Development Association (Shaanxi Province) is one of YiNongDai’s first batch of partners. In 2005, the Association received a donation from Plan International to provide micro-finance services to local towns. However, without new funding sources, it became very difficult for the Association to increase its own funds. Since the Association cooperated with YiNongDai in 2009, the accumulated funds obtained from the YiNongDai platform have already exceeded the amount of financial assistance received from Plan International.

Aside from providing fund for non-profit MFIs, YiNongDai also help them achieve sustainable development. Starting in 2014, YiNongDai began to encourage these institutions to help improve the infrastructure of local villages. In 2014, YiNongDai cooperated with the Grameen Foundation and the Beijing YouChange Foundation to launch the “China Poverty Scorecard Pilot Training Scheme”. The scheme is to provide instructions to YiNongDai’s partner organizations on how to use the poverty scorecard, help non-profit MFIs to measure and confirm targeted beneficiaries’ level of poverty, and monitor their progress against poverty. YiNongDai encourages these organizations to facilitate the rural community construction, such as providing training in agricultural technology, reinforcing the capacity-building of rural women, improving rural infrastructure and so on. Furthermore, YiNongDai requires these organizations to satisfy the requirement of “Public Interest Value Labels”, including “Women’s Empowerment”, “Education Support”, “Community Services”, “Business Support” and “Environment Improvement”. After being assessed, these labels will show the extent to which MFIs carry out public interest activities in the local community on the website, They can also reflect the impacts and contribution of MFIs on the local community more directly. As of May 2015, YiNongDai platform has loaned out 120 million RMB to more than 14,000 rural women. Without the help of these non-profit MFIs, YiNongDai would not have been able to perform and finish its work in such a short period of time. CSR Manager Guo Xiaorui of CreditEase describes this relationship as: “we are like two people on the two sides of the same river, who are now swimming towards the middle of the river and will meet together one day”

YiNongDai is CreditEase’s first online financial product targeting rural villages and has achieved incredible success. However, due to the limited number of non-profit MFIs in China, CreditEase soon introduced a new business project called NongShangDai, in order to allow more farmers benefit from Inclusive Finance. Through establishing its own service network in rural villages, NongShangDai is able to provide its services to more extensive rural markets. One difference between YiNongDai and NongShangDai is that the latter offers higher credit limits with wider coverage of service areas. Its target customers include urban entrepreneurs and people engaged in new rural construction. NongShangDai even explores business opportunities in new rural financial services such as supply chain finance and land circulation, and adopts the risk-based pricing rule, so as to satisfy the developmental needs of economically active farmers. Since 2011, NongShangDai has provided over 800 million RMB of credit loans and become a self-financing business unit of CreditEase. Although NongShangDai is one of the commercial products of CreditEase, it has a real impact on farmers’ lives. It lifts the idea of “peasant enrichment” to new heights on the basis of poverty eradication, and embodies the double bottom line of both business and social value that CreditEase is pursuing and advocating.

YiNongDai still maintains its non-profit nature and is written into CreditEase’s long-term strategic plans as a sustainable development project of the company. Unlike many other businesses which marginalize their own CSR departments, YiNongDai has become one of the core departments of the company. A substantial amount of internal resources in relation to capital and office space has been devoted to it. YiNongDai also gets its own independent project accounting and audit. With the efforts of nearly 30 team members, it will continue to provide assistance to poor rural communities.

CreditEase’s CSR practice gives us an insight into the trend that companies can actually combine their business models and core businesses with CSR, making full use of their competitive resources and the power of professional NGOs and NPOs, and eventually achieve balance between social and business impact.