Editor’s Note

This article was originally published by the China Lingshan Council for the Promotion of Philanthropy (中国灵山公益慈善促进会) on the 27th of June 2018. Below is CDB’s translation.

The following content was complied on the basis of the talk given by Chinese Academy of Social Sciences researcher, Centre for Social Policy Research advisor and Blue Book of Philanthropy chief editor Yang Tuan at the “2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit with the 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference” on 20th June. The content has been examined by the author.

1. Statistics on the development of Chinese charity in 2017

The data provided in the 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy allows us to get a general picture of Chinese charity and philanthropy in 2017.

First of all, in 2017 China’s total private donations were estimated at 155.8 billion RMB. Due to the delay in government and industry data collection, the Blue Book of Philanthropy calculates totals using an annual rolling method, announcing every year the confirmed total for two years prior and the estimated total for the previous year. Therefore, the data for 2017 is an estimate made by the Blue Book of Philanthropy using partial data and data calculations to collate data on the development and trends of the charity and philanthropy sector.

However the figure for total donations in 2016, 145.8 billion RMB, was obtained through various statistical corrections of raw data to calculate the final total, and the 2015 total of 121.5 billion RMB was calculated in a similar way. In light of this, the estimated total donations for 2017 shows continued growth compared to 2016 and 2015, but the growth rate is only 6.86%, the lowest since 2012.

(graphics from the presentation at the “2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit with the 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference”)

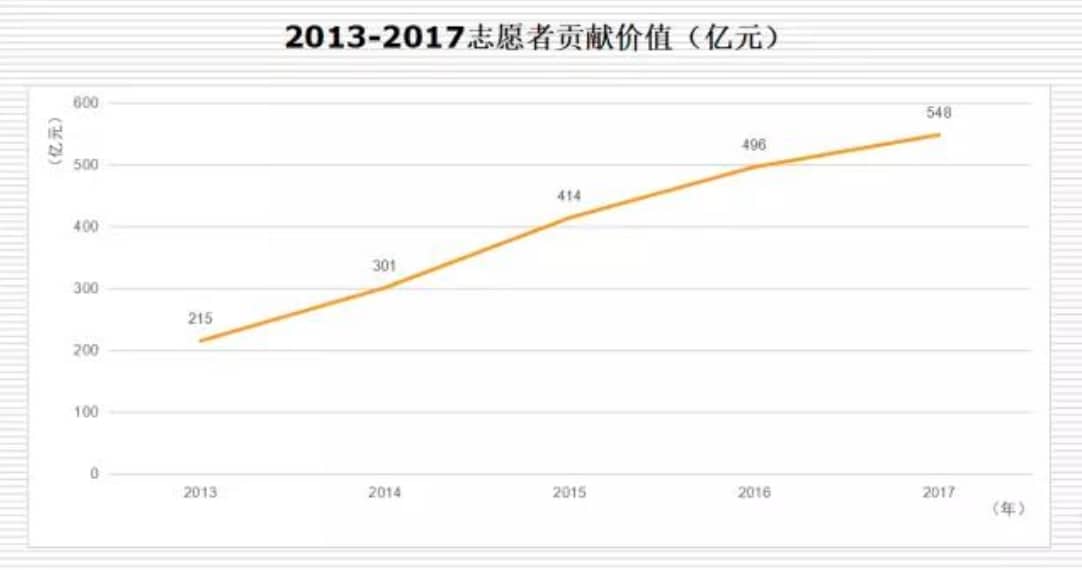

Second of all, the value of China’s volunteering hours in 2017 was calculated at 54.997 billion RMB, a growth of 10.48% compared with 2016. Since 2014, the Blue Book of Philanthropy has stimulated research measuring Chinese volunteering, and drawing from leading overseas research on volunteer services it has developed indicators of the development of Chinese volunteering. Not only does this take into account the value of the time contributed by the volunteers as a major contribution to charitable causes and thus the philanthropic sector; it also directly promotes the integration of Chinese and international measurements of voluntary services, from which long-term and stable professional and research sectors can emerge.

In 2017, the total number of volunteers in China was 158.0734 million people, of which 60.9266 million were active, with a participation rate was 8.7%. There were 1.3067 million voluntary service organizations, and volunteer service time was 1.793 billion hours.

(graphics from a presentation at the “2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit with the 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference”)

Third comes the money raised through public welfare lottery funds. Starting in 2015 the Blue Book of Philanthropy increased its reporting on the topic of China’s lotteries and the development of philanthropy, explaining the history of the modern Chinese lottery since 1987, the money collected through the public welfare lottery fund and its utilisation. Since then there has been continuous follow up and research done annually. Statistics show that China’s accumulated public welfare lottery funds were approximately 114.326 billion Yuan in 2017, a growth of 10.03% compared to 2016.

The Blue Book of Philanthropy suggests a new statistical approach, which is to take the sum of the annual total donations, the calculated value of volunteer service time and the money raised from the public welfare lottery fund, in order to calculate that year’s “total assessed social charity value”. Calculating in this way, China’s 2017 total assessed social charity value is estimated at 324.923 billion RMB. Compared to 2016 there is a 8.56% growth, but the growth rate has fallen by around 6.2%.

(graphics from a presentation at the “2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit with the 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference”)

The total number of social organisations in China in 2017 passed the 800,000 mark, reaching the figure of 801,083. Out of these there were 6322 foundations, 373,194 social groups and 421,567 private non-enterprise units. (These totals come from big data analysis. The data on nationwide social organisations comes from the registration information systems of the Ministry of Civil Affairs, and for local social organisations the data comes from the national social organisation unified social credit code system. The data is continuously updated – last update: 11 April 2018.)

2. Reflections on the basic characteristics of the development of Chinese philanthropy

The Blue Book of Philanthropy summarises the basic characteristics of the development of Chinese philanthropy in 2017 with the following words: 负重前行, or “shouldering the heavy load and moving forward”. More specifically:

1. Overall the number of social organisations has continued to grow, but the growth rate of the three major types of organisations has been unsteady.

2017 was the second year of implementation of the Charity Law and the Overseas NGO Law. In the less than two years that these laws have been implemented, the number of China’s social organisations has continued to grow, but there has been a change in the growth rate. As seen in the graphic below, the growth rate of foundations has seen a significant fall, while the growth rate of social groups and private non-enterprise units has seen a small increase.

(graphics from a presentation at the “2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit and the 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference”)

There are two reasons for this. The first one is that there has been a gap in terms of institutional cohesion, especially since some key supporting systems that should aid the implementation of the Charity Law have yet to be introduced, for example, the management regulations for the three major types of social organisations (foundations, private non-enterprise units and social groups), resulting in a lack of compliance from the relevant government departments. Secondly, while supervision of social organisations is being increased, gaps in the knowledge of some departments have occurred. I have heard of some relevant people in charge of departments say, “we already have too many social organisations, we don’t manage to supervise them all, why are they still establishing more?”.

2. The change in the pattern of the supply side of the charity market has been unstable

When the 2017 Blue Book of Philanthropy was published last year, I said that the pattern of the supply side of the charity market was changing. This year the trend is even more obvious, the supply side of the charity market presents an unstable pattern. This is to say that the situation is not always good, and a lot of new problems have emerged that could never have been foreseen.

For example the internet fundraising market was making triumphant progress in 2016, but in 2017 it repeatedly came into question, with the issues surrounding Tencent’s 9/9 Philanthropy Day, including machine-generated fundraising, yet to be clarified. Furthermore, there is the issue of the private sector attempting to get involved in charitable work; although some major tycoons have made great efforts, on the whole most of the private sector seems to be observing from the sidelines, and the main reason for this is the lack of policy support, especially in the case of equity donations. Moreover, those foundations whose name is prefixed with a 中 (zhong – the indicator term for China)1, with the exception of a few special cases like the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation, have shown a definite declining trend; since 2017, foundations have gained the encouragement and support of the central government, but development coexists with problems, and in some regions administrative interference has taken up a dominant position. Within the field of modern charity, science and educational work and environmental protection are obviously increasing in importance, but there is considerable overlap with the work of technology, industry and commerce, which is a demonstration of the changing patterns of the supply side of the charity market.

In regards to the changing pattern of the supply side of the charity market, one last thing that deserves a mention is the rapid development of community charity. Community charity is informal, unregistered philanthropy, and it includes web-based charities. The rapid development of this type of philanthropy is creating new developments and highlights for the future. Due to its unique adaptation to the centralization of the online age, its growth has been rapid. However, at the moment its growth lacks the direction and supervision of regulations.

The unstable pattern on the supply side of the charity market can be understood as a normal phenomenon which comes with the drastic transformation of China and the world. The transformation of China’s general set-up is the new economic norm, moving from high-speed growth towards medium to low speed, and from the single minded emphasis on quantity to an emphasis on the development of quality. This has inspired reform on all sides, including within the charity and philanthropy sector. On the international stage, which is represented by China and the US, there may be a long-term contest between the paths of global cooperation and of unilateral hegemony. The range of problems that has emerged during the reform of the supply side of China’s charity market I believe is a natural result of wider changes that are taking place.

However the philanthropic sector, as a part of the wider world, lacks the analysis and strategic planning to deal with the changes happening around it. Philanthropy is not simply an isolated field, but a human creation infused with the spirit of the age’s politics, economy, society, culture and education. Whether it can meet the new challenges coming form the changing domestic and international situation, and take hold of the new opportunities brought by these changes, is crucial to its future.

(Yang Tuan at the“2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit and the 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference”, photo taken by Shen Zhijia)

3. A new type of philanthropy is emerging, modern philanthropy is exploring new paths

Another important phenomenon in 2017 is the philanthropic sector’s exploration of new paths.

The first path is rural development. Rural development has in reality given Chinese philanthropy a huge opportunity. Within rural development, not only is there work to be done on poverty alleviation, or providing the elderly, women, and children with social support, but more important is whether civil society has the ability to enter the core areas of rural development and carry out ecological improvements, create industrial prosperity and in the process motivate the local farming communities to cooperate, creating a change in the foundations of the urban and rural societies.

The second is cultural philanthropy. How can modern and traditional cultures, the humanities and ecological sciences be brought together is a big question. Ecology and the humanities are two fields that don’t overlap, one deals with the natural sciences and the other with the social ones. For millions of years the development of agriculture has in fact been driven by the cooperation of these two fields, but in the industrial era ecology became a way to decodify the manufacturing technology industry, completely separated from the humanities, leading to an ecology divorced from humanistic concepts, lacking vitality and motivation. Cultural philanthropy takes a wide cultural perspective, reintegrating humanities and ecology, to go as far as creating an ecological humanities discipline that can sustain China and the world’s march towards an ecologically civilized era.

The third is the Belt and Road Initiative. In actuality the Belt and Road represents how China faces the outside world, how it can face the global goal of building a community of shared future. In the midst of this, do philanthropy and social organisations have an advantage? Who to partner with and how to proceed? These are all questions that require in depth consideration.

The fourth is having to deal with complex relationships at multiple levels. As traditional philanthropy turns into a more modern form of non-governmental charity, there is a need for a universally applicable rule to deal with the relationship between philanthropy and business. To do this we need to break with traditional thought and take new ideas in a new direction. The 2017 “two lights debate” (亮光争论 liang guang zheng lun), is currently testing the waters of breaking those traditional thoughts. The debate is not simply a personal disagreement, but the demonstration of a clash between two different ways of thinking that is a necessary part of the development of modern philanthropy. In the changing pattern of the supply side of the charity market, what direction should Chinese charity and philanthropy take? Can it not go to extremes and rather take a middle road – this is a question that needs to be considered seriously.

Over the past ten years, the questions that we used to constantly consider have become less important, but new questions have emerged.

For example, what is philanthropy? What is charity? What is the relationship between the two? Nowadays it seems that answering these questions is not as important as it used to be, because modern non-governmental charity can include traditional philanthropy.

Furthermore, what is the relationship between the government and philanthropy? It seems that making this distinction is also not as crucial as it used to be, but rather cooperation is. The government has already demonstrated a commitment to learning, purchasing the services of social organisations, expressing hopes that charitable organisations and social organisations can be a part of the innovation and reform of social governance, etc… It is in fact the willingness and ability of non-governmental organisations to fulfil these demands that has not been fully demonstrated. This cannot simply be blamed on the incompatibility of the general environment, because if one is not prepared even if the opportunity comes along it cannot be seized, and what social organisations can achieve has been demonstrated in the field of rural development. The government and general environment cannot always take the blame, and non-governmental organisations also need to reflect on themselves.

Personal charities and organisational charities, public donations and personal donations; should the line between the two be clearly drawn? It seems that the urgency of this question has also weakened. In the internet age individuals can casually create groups, generating lots of non-registered, community-based alliances and platforms that can carry out informal philanthropy. This shows that the lines between types of charity are being blurred thanks to these new cooperations and the generation of new communities.

Are there clear boundaries between charitable organisations and commercial ones? From the current perspective, it seems that this boundary needs to be drawn, but cooperation is vital, and in the end, is it drawing boundaries that is important or cooperating and doing things together, then identifying and tackling issues within the operation? How these two sectors can be integrated to become a community-based organisation that does things together – this may be an innovative direction in which traditional Chinese wisdom and culture can be made use of.

(Photo from the “2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit and 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference”, photo taken by Shen Zhijia)

3. Looking forward to the next ten years of Chinese philanthropy and charity

All in all, Chinese philanthropy can seize the opportunities generated by the structural changes in China and abroad. China needs to look forward, develop a prosperous society on all fronts and participate in the building of a common human destiny. Changing from focusing purely on economic growth to focusing on the overall construction of high-quality development requires China to adapt and change in all aspects, including the philanthropic sector. This is an opportunity, and at the same time a historic challenge. In order to face this challenge, the questions of how Chinese philanthropy will reform its structures, obtain technologies, increase its vitality and remain close to reality are all questions that today’s “2008-2018 China charity ten year summit and 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference” needs to pay specific attention and consideration to.

I believe that the most important think is to break out of the exclusive “philanthropic circle”, and enter the platforms and coordinated actions that the government, industry, education, research and society are discussing together. Non-governmental organisations have their own unique advantages, and at the same time they need to push other sectors to make use of their own advantages. This will probably be an important new direction of development for the coming ten years.

To do this well, it will be necessary to work diligently under the Charity Law, creating stronger and more targeted platforms and community-based organisations.

The famous sociologist Xiao Tongzeng (孝通曾) came up with a celebrated saying regarding China’s direction in the world: “ge mei qi mei” (各美其美), meaning that everyone can bring out the talents and strengths in each other, “mei ren zhi mei” (美人之美), meaning one should appreciate the strengths and beauty of others, and “mei mei yu gong” (美美与共), meaning that all the good, all of the strengths of everyone put together can create a great community, and only in this way can the reality of “harmony in the world” (tian xia da tong – 天下大同) be realised.

(Presentation of the tenth anniversary edition of the Blue Book of Philanthropy at the “2008-2018 China civil society ten year summit an 2018 Blue Book of Philanthropy publication conference”, photo taken by Shen Zhijia)

Notes

1) The use of the term “China” in organizations’ names is restricted. Foundations prefixed with the character 中 are thus likely to have a strong government background.