Editor’s Note:

the case of Luo Er and his attempt to raise funds for his ill daughter was certainly one of the most discussed incidents of 2016 in the Chinese charity sector. The basic facts are as follows: at the end of November an article pleading for help written by one Luo Er, a man from Shenzhen whose daughter Luo Yixiao was unfortunately suffering from leukaemia, went viral on Wechat. A very large sum of money was raised within a day, but very soon doubts started to be raised about the situation: people accused Luo Er of misrepresenting his financial situation, while the company that was behind the initiative also fell under suspicion. CDB reported on the affair here.

We have translated this article by Southern Weekly, analyzing the whole incident and its implications for China’s charity sector. In the meantime, it has been reported that little Luo Yixiao tragically died on Christmas Eve.

Yesterday the name “Luo Yixiao” was to be found all over Chinese social media on three separate occasions.

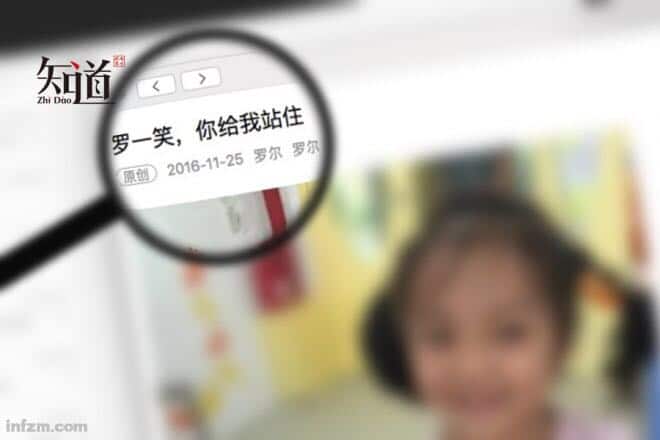

First the article “Luo Yixiao, stop right there” was reposted by a large number of people on WeChat Moments. The article explained that Shenzhen writer Luo Er’s 5-year old daughter Luo Yixiao had been diagnosed with leukaemia and admitted to the Shenzhen Children’s Hospital. Her medical fees ranged from 10,000 to 30,000 Yuan per day. Her father was terribly anxious, but he did not choose to ask for public donations, and decided instead to “sell text”. This means that each time the article was re-posted, the Xiaotongren Company would donate 1 Yuan to Luo Er, for a minimum of 20,000 Yuan and a maximum of 500,000 Yuan.

But just a few short hours later a reaction emerged, with a large number of screenshots casting doubts on the Luo Er’s story as it appeared in Wechat. In the main, there were four aspects of the story which were being taken issue with.

First of all there was Luo Er’s marriage history and private life, but we omit that part here as it involves issues of privacy and veracity;

Secondly, it was claimed that Luo Er’s family is actually well off. He had previously written a public article in which he claimed to have three houses in Dongguan and two cars. In addition, he owned a company with shining prospects, so his economic situation was actually quite good;

Thirdly, Luo Er wrote in the article where he asked for help that his daughter’s daily treatment and medical expenses reached dozens of thousands of Yuan, and his family could not afford them. However, information posted by netizens showed that close to 80% of Luo Yixiao’s treatment was reimbursable, and the portion paid by Luo Er himself had been exaggerated;

Fourthly, behind the scenes of Luo Er’s plea was a P2P company engaged in self-promotion.

Just as Luo Er began to face the public’s wrath, he appeared in public interviews, in which he responded to some of the doubts, turning things around once again so that the story went as follows: first of all, regarding the stories about him owning three homes, he explained that he bought the first property in Shenzhen paying 200,000 Yuan in full in 2001. Afterwards, he bought a hotel-style apartment in Dongguan and a 3-bedroom 80 sqm house in Changping totalling 1,000,000 Yuan with a bank loan of 400,000 Yuan and monthly payments of 5,000 Yuan.

At present he does not have the titles to the two properties and thus cannot sell them. The family only owns one Buick bought for 100,000 Yuan in 2007. He has never set up a company, and since the publication “Women’s Story”, of which he had been chief editor, went out of print in 2016, he has only being receiving a monthly salary of 4,000 Yuan. His wife is a full-time housewife, and the family has no other sources of income. The article he had previously written on the Internet was “fictional.”

Secondly, regarding the cost of his daughter’s treatment, according to the Shenzhen Children’s Hospital’s notice the fees for Luo Yixiao’s three hospitalisation were some 200,000 Yuan, and to date the portion Luo Er’s has to pay himself is nearly 40,000, with the remainder reimbursed by medical insurance.

Thirdly, regarding the issue of it being a promotional ploy, Luo Er explained that he is friends with the management of the P2P company. He accepted this method of donation only because he did not want to directly accept friends’ donations in cash, and he did not understand the marketing spin.

The facts of the matter may be subject to further reversals, but one thing is for certain: aside from the unfortunate fact of Luo Yixiao suffering from leukaemia, some of the claims in Luo Er’s article are patently false, such as the following claim: “the cost of the intensive care room is tens of thousands of Yuan a day, she is pained that we cannot afford the costs, and what is even more painful is that even spending that money may not save Xiaoxiao’s life.” All the same, him and the P2P company in the background have collected more than two million Yuan in donations.

Purely from the perspective of charity, Luo Er’s private life should have no bearing on his eligibility to receive donations; however, his daughter’s condition and treatment costs were the impetus for people to donate, and Luo Er’s actions amount to deceit. Even if he was not liable under the Charity Law because his acts were committed in a personal capacity, he is worthy of condemnation on a moral level. As for the P2P company, which did not have the right to make donations, its violation of the Charity Act amounts to fraud.

A diversity of opinions surrounds this issue. There are those who criticise the flippancy with which posts are shared, and the inflated sense of righteousness of the donors and their use of money to show support, and feel that they deserve to be deceived. However, there is a more universal and pertinent issue that bears considering: whether online requests for fundraising are trustworthy, and how we are to demonstrate our support for charitable causes online.

The benefits of using the internet as a medium for fundraising do not need further elaboration. It gives the disadvantaged a voice by providing them with a platform to express themselves, and is an effective way of raising funds over a short period of time. It has helped a lot of people, but it is a double-edged sword, given that there are too many issues with fundraising activities online.

The first issue is that philanthropy is a specialist area which requires consideration of the validity of fundraising requests, and the allocation and the utilisation of funds. In addition, given that the sources of funds are limited, the question also arises as to who is more deserving of such aid.

However, the current online fundraising environment lacks any of these systems and processes. Stories are given veracity and shared freely on the back of a few photographs, a few emotional sentences, and a few endorsements from friends. In the Luo Yi Xiao incident, no details were ever released of the child’s diagnosis, condition, family background, and yet the fundraising post was shared thousands of times and received thousands of donations. Similar incidents, like the “Big V Tong Yao” fraud and the incident where an individual passed himself off as the son of a fireman who sacrificed his life in Tianjin, bear testament to the difficulty in ascertaining the truth of what is posted and the lack of regulations on the internet.

It may also have escaped our attention that emotions are easily fanned online. Our perception of reality and emotions are shaped by the media. The protection afforded by virtual reality means that triggers for emotions – whether they be sympathy, concern, being moved, anger, anxiety, or violence – are lower than in real life. This can be exploited by crooks to their own advantage. A few sensational articles then suffice to fan the feelings of righteousness of many netizens.

In short, the drawback of online donation-raising and help-seeking is that it has not been standardized and the public is not discerning enough, therefore there is a high possibility of deception. Observer of the charity sector Zhang Tianpan summarizes things like this: “(all the cases of fraudulent fundraising on the internet) stimulate the emotions of the public and then generate donations and public attention. People do not try to identify the authenticity of the information, in fact they do not even think about it. To deal with this problem, he advocates that “we should let charity achieve the maximization of public interest instead of allowing the person who can tell the best story to enjoy all the benefits”. He also advocates that donations should be made through professional charitable organizations, so that they can be used in the most regularized way possible, and more people can receive the benefits.

The development of Chinese charitable organizations however is currently still in the startup stage. The regional distribution is not balanced and the ability of organizations is still limited. A great number of people need help, but they are unable to find a way to receive help from others. In this case, platforms like “Easy Fundraising” can be an effective supplement, with their functions to offer assistance for fundraising and personal help-seeking.

The problem is how to achieve the standardization of the charity sector and how to prevent people’s kindness from being abused. The article “how much love can maliciously be squeezed out like this?”, published on the official Wechat account of Southern Weekly, provides some possible ways to address the existing problems. For example, help-seekers could be duty-bound to publicize their own income and properties, and also those of their children if they have alimony obligations, and deceivers would be punished; they could also publicize their hospital records and related certificates and provide ways to verify them, in order to let everyone easily ascertain the information’s authenticity; besides, there should be a best treatment plan and estimated medical expenses should be assessed by third-party professionals. We also hope that the Charity Law can address these issues.

In a word, we truly hope the child Luo Yixiao can be well and healthy. And we also hope that this event can push the public to discuss and solve the problems related to online fundraising and help-seeking, so that people’s kindness will not be taken advantage of, social trust and resources will not be overdrawn and more and more people who genuinely need help can enjoy other’s friendship and cooperation.

Note: in this discussion, many people are confused about the differences between personal fundraising and personal help-seeking1. In a nutshell, personal fundraising has got to be “beneficial to others”, meaning people other than the help seeker and their close relatives, while personal help-seeking is “beneficial to oneself”, in other words only to the help seeker or their close relatives. The Charity Law allows personal help-seeking but forbids personal fundraising. In this case, the behaviour on Luo Er’s Wechat account was personal help-seeking, which is legal. However, the P2P company had no qualifications to raise funds. This was a breach of the Charity Law. Furthermore, both of them stretched the facts about the treatment’s expenses and covered the truth regarding reimbursements. As a result, their behaviour was very likely to constitute fraud.

1The terms used in Chinese are 个人募捐 and 个人求助