The authors of this article, Ms. Cathy Cao Xi and Ms. Isabel Nepstad, are agricultural experts based in Beijing. They provide consultancies to international organizations and agri-businesses on China’s food governance and e-commerce. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone.

The Wuhan coronavirus, also named 2019-nCoV, has entered a severe and complex stage in China, and even worldwide, since its outbreak in January. By January 28th, China’s National Health Commission confirmed 5974 cases of pneumonia diagnosed with new coronavirus infections in 31 provinces, including 1239 severe cases, 132 deaths, and 103 cured cases. A total of 5794 suspected cases were reported in 30 provinces [1]. Although the government of Wuhan has suspended all public transportation and closed its airport and railway stations to outgoing passengers on January 22nd, the fact is that thousands of “likely” infected cases may already be spreading around China during the peak travel season.

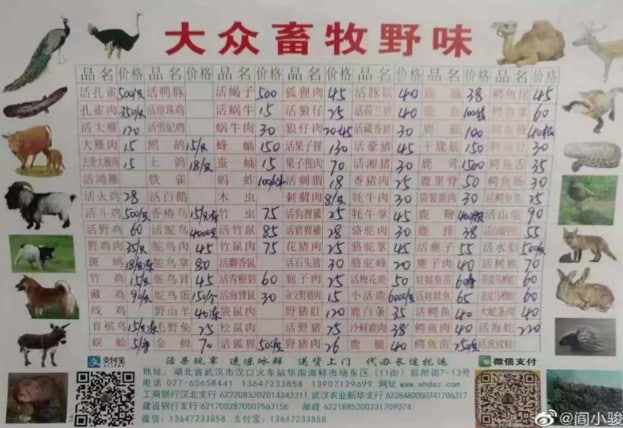

Tracing the origins of the Wuhan Coronavirus, the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan is thought to have been the starting point for the outbreak. Photos posted on social media indicate that the Huanan Seafood Market, a wet market, was selling live and wild animals such as peacocks, hedgehogs, wild rabbits, civet cats, and even crocodile meat. Officials do not yet know what animal from the wet market is associated with the current outbreak, but it is assumed the virus spread through animal-to-person contact. If we look back at SARS, scientists suspected at the time that civet cats in Guangzhou’s wet market were to blame.

In China, the New Year dinner has always been the most significant part of the celebrations for the Chinese Lunar New Year. According to a common attitude, the rarer and more expensive the meat on the table, the merrier. Wild animals are also considered more natural, and thus nutritious, compared to farmed meat. Many Chinese hold a belief, based in traditional Chinese medicine, that eating these rare meats can boost the immune system. However, the wild animal trade saw a temporary ban during the year of Rat, shortly after the outbreak of the Wuhan coronavirus. To cut off the possible means of transmission, the General Administration of Market Supervision, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and the State Forestry and Grassland Administration issued a notice to temporarily ban the wild animal trade across China [2].

At the same time, the China National Health Commission is alerting residents not to consume wild animal meat. A number of citizens have claimed on social media that they are now only eating vegetables during the holidays, as a measure to protect themselves from the infection. The tracing of the Coronavirus and citizens’ distancing themselves from meat inevitably brings our attention to food safety in China, a topic that has been much discussed amongst the Chinese over recent decades.

Although the state has made numerous efforts to tackle food safety, such as publishing new guidelines on food safety standards in 2019, the safety of the food in practice and in daily life is still worrying. For instance, it is unclear what the definition of wild animals is, as well as how the trade in wild animals can be traced or regulated. The wet markets, or open-air markets, which are widely situated in many corners of cities and towns, are believed to be the predominant food-retail outlets for the wild animal trade in China. After the 2003 SARS outbreak and the 2019 African swine fever, there has been some crackdown on selling wild animals in wet markets located in Guangzhou and Beijing. But in many other large cities, the trade still goes on.

What keeps people coming? Apart from the Chinese culture of wealth and nutrition, there is also a cultural value attached to “freshness”, coupled with an aversion towards “non-fresh” or frozen food. Wet markets typically consist of wholesalers and food vendors as well as consumers. Within a fragmented and unregulated food trade system, the small-scale food vendors in wet markets are able to offer “fresh” food with a reasonable price by shortening supply chains, due to the vendors’ personal connections with wholesalers, agencies, and middlemen. In this scenario, the evaluation of food safety is based upon the trust between consumers and food vendors. Consequently, this allows little space for tracking food safety and regulating the food standards along the relationship-based supply chains in the wet markets.

Everywhere, developed countries such as the U.S. and Sweden have encountered issues with food-borne diseases and food safety related to wild animal consumption. Consumption of “fresh” and wild animals is also seen in parts of the U.S. and Europe, but with tighter regulations.

In Scandinavia, hunting is a popular sport and wild game, including reindeer and moose, is a local delicacy. In Sweden, for example, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Environmental Protection are responsible for hunting and wildlife management. Citizens interested in hunting must complete trainings and take a test in order to receive a hunting permit. With a permit, hunters are only allowed to hunt certain animals during designated seasons. Wild animals, in the law, are defined as animals that live freely in the wild as a native species to the region. The Ministry of Environmental Protection of Sweden has strict enforcement and a step-wise approach for managing and monitoring the hunting of wild animals [3]. This includes maintaining an information system to share updates on wild animals, education of consumers, and cooperation with neighbouring countries. Sweden has a special origin label, “Meat from Sweden”, for meat products in grocery stores and dishes in restaurants [4]. This allows consumers to have recognition and build trust in local products.

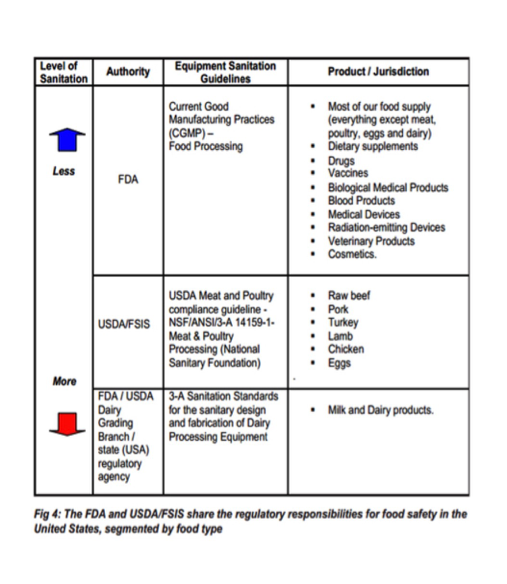

In the United States, fishing is both a recreational and commercial activity. Regulations on hunting and fishing are defined and enforced at the state-level. In the state of Massachusetts, famous for Boston Lobster, it is required by law that individuals obtain a permit for fishing or catching lobster, shellfish or other seafood products [5]. If an individual wants to sell his “catch-of-the-day”, this requires an additional commercial fishing license. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) have established strict regulations and standards on food safety to oversee the whole supply chain from farm to table [6]. The USDA and the FDA work together to provide guidelines and regulations for the proper production, processing, distribution and labelling of food products for businesses, but also to educate the public on food safety measures so they can be responsible consumers.

Following the outbreak of the virus, the Chinese government has been proactively helping the citizens infected, and it has also placed a temporary ban on the trade of wild animals in an effort to curb the spread of the virus. We commend all of the efforts made to address the viral outbreak. Considering the lessons learned from other countries, we suggest the following recommendations for consideration:

- The authorities develop comprehensive policies and regulations on the supply chains in wet markets to make sure that there is no food-safety risk, especially regarding wild animals and live chickens, for example; The regulations include clear definitions of wild animals, of what can be traded and by which means.

- The concerned parties set up a public and transparent information system for disclosing information on animal products to the food industry and consumers. In particular, the list of wet markets and certified food vendors/shops can be released to the public, and particularly to buyers.

In the specific context of China, educating the domestic consumers is also of vital importance:

- Measures should be taken to raise consumers’ awareness about food safety and labelling. Eating wild animals is considered a symbol of wealth in Chinese culture, because they are more rare and expensive. It is of critical importance to reshape these misconceptions widely shared within communities.

- The hygiene of fresh food is another concern. Action ought to be taken on informing and training consumers about disinfection and sterilization when cooking fresh food.

Due to the current scale of the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak, and to avoid the emergence of other new viruses, there is a strong call for food safety in China. The goal of achieving a safer food system for China necessitates long-term efforts, and this will require a joint effort by the government, citizens, the private sector, and other actors in play.

[1] http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202001/9614b05a8cac4ffabac10c4502fe517c.shtml

[2] https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/vXooZecmg8hJql8uHA1RJQ

[3] https://www.naturvardsverket.se/Documents/publikationer6400/978-91-620-8797-5.pdf?pid=22001

[4] https://fransverige.se/in-english/

[5] https://www.mass.gov/recreational-lobster-fishing

[6]https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2018/05/30/usda-and-fda-cooperation-continues-ensure-safe-food-supply