This is part two of CDB’s interview with staff from the Wei Lan Library initiative. You can read part one here.

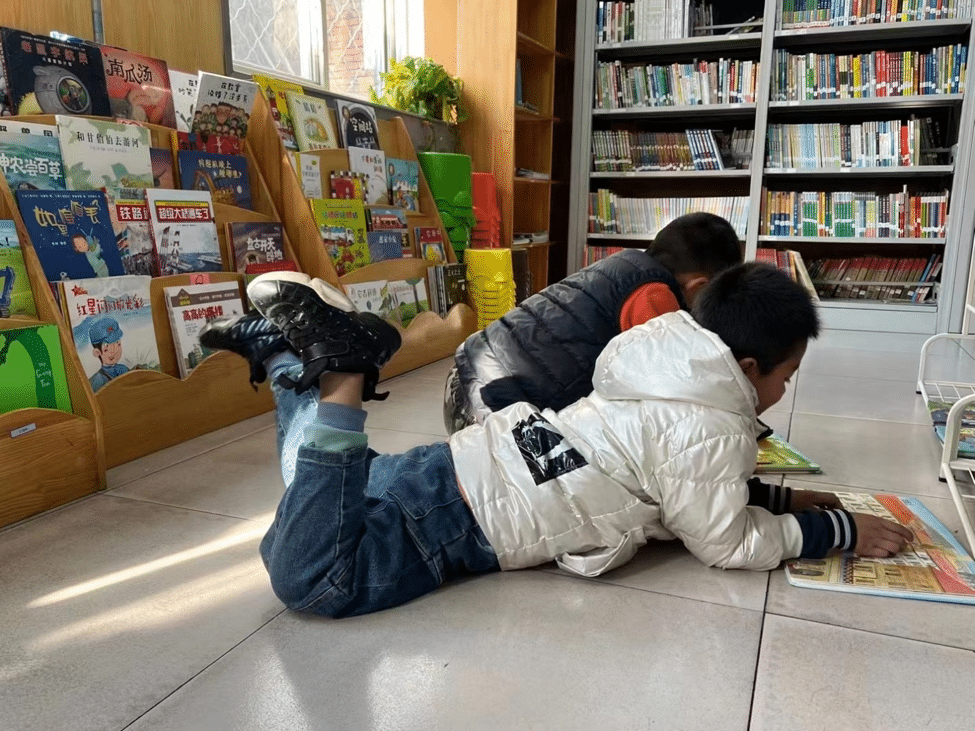

Wei Lan Library doesn’t just provide books, it provides a public space for children to build connections with their peers and library volunteers.

“At home, some of the children might not have much communication with their family. Parents are focused on trying to make ends meet; or they tend to only focus on children’s academic performance and neglect their emotional needs and communication skills,” said Liao Xixiong, director of Beijing Sanzhi Center for Unprivileged Children, which set up the library initiative.

Indeed, there are other libraries and bookshops in cities that are open to the public, but interactions between people are often discouraged. “Here at our library, we want to see children communicating and building relationships with their peers and other adults. That is an important part of their social-emotional development.”

One teacher surnamed Ma at a LFP school in Beijing’s Chaoyang District told CDB that children in her school love their Wei Lan library.

“In the past few weeks, the library has been closed due to a new COVID-19 outbreak. When the children found out that it had re-opened today, they were so excited and eager to share the news with their friends,” said Ma.

She has also noticed the difference in children’s reading patterns and abilities since the library started operating.

“When the library was first introduced, most of the children would run to borrow the comic books. But now, many children from grades five and six (aged 11 to 13) will choose to borrow books related to culture, literature and society. Younger children who are starting to have science classes are picking books about the universe or modern technologies to complement what they are learning in the classroom.”

Ma said that sometimes, students would also ask Wei Lan’s staff and volunteers for new books. “The library pays attention to what our students want, and once they receive a book request, they will do their best to get it into the library. When a child sees her friends borrowing books and reading them, she will follow suit.”

Currently, there are five full-time staff at Sanzhi who focus exclusively on the Wei Lan Library program. Staff who have responsibilities in other areas will occasionally give the program a hand when they can. Thanks to modern technology, this small team is able to access an online database where they can keep a track record of the libraries, the volunteers and books quite easily. But Liao pointed out that the “human side” of the work actually matters much more. With a background in management and client communications, she believes that serving “internal clients” through communication is as important as serving external clients.

Of course, the internal clients are Liao’s colleagues and volunteer teams at Wei Lan who work on various tasks and in different locations. She feels it is vital to bridge the information gap between different teams and encourage different libraries and teams to share their experiences – good and bad. That way, the progress of the whole program will be more transparent to each staff member and volunteer, and they will not lose sight of what they are doing and how they contribute to the whole program.

Soon after she joined Sanzhi, Liao set up a Wechat account named “Xiao Xin” to keep in daily contact with individual workers. People can use the account to ask questions, give her feedback and make suggestions for improvement. When people encounter upsetting things at work, Xiao Xin will give them encouragement and try to offer solutions.

This people-centered, relationship-based communication service is what Liao considers to be “effective communication”. But she admits that ineffective communication is common.

“During my two-year volunteer program with Wei Lan, I also spent time taking part in many public events run by other organizations. One thing I observed is that communication between the host and the audience was mostly one-way: the host had something to say but the audience found it hard to relate. This kind of communication is fine for passing on information but fails to connect people.”

As the director of communications at Sanzhi, Liao also maintains this principle when promoting the organization and its programs to external clients.

“As a nonprofit organization, each time when we communicate, we hope to show our subscribers and potential partners the following two things in a clear manner: what social problems we are solving and how we solve them. For the Wei Lan Library program, we want our audience to know the real stories of migrant children and LFP schools, and the actions we are taking. I hope our work can inspire people to take action in the knowledge that their help will make a difference, no matter how small it is.”

So far, more than 3,000 volunteers have registered for Wei Lan’s services and approximately 69,000 migrant children have been reached by the libraries. While some believe that the commercialization of charitable work represents the future of the voluntary sector, Wei Lan Library has no plans to go down this path.

“What our libraries focus on is children’s education, and we do it for charity and not for commercial benefit. Luckily, our partners and supporters all recognize that this is our bottom line. And equally, I appreciate that my colleagues hold the same values – the values which keep motivating us to serve migrant children.”