Editor’s Note

The author of this article was a licensed social worker in Hong Kong and Singapore. She provides consultancy to international organzations on China’s social policy, food governance, and e-commerce. At point of writing, she is staying in Hubei province and providing supervision for volunteers involved in online support groups. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

New cases of COVID-19, better known as the coronavirus, have recently shown a downward trend in China. Although the situation is now stabilizing, the virus has infected 80,409 people, caused 3,012 death, and left at least 25,352 under treatment within the country1. Outside of China, over 30 countries have detected Covid-19 cases, with Iran, Japan, South Korea and Italy especially badly hit.

After the COVID-19 first broke out in its epicentre of Wuhan, the local authorities put the city under lockdown on January 23. The sudden shutting down of public transportation, cancelation of flights and trains and closure of schools and factories did not take place in Wuhan alone; almost all the cities in Hubei province and other neighbouring areas followed suit during the holidays for the Lunar New Year. The national government subsequently announced the extension of the Lunar New Year Holidays to further prevent the spread of the virus amongst travellers.

In order to cure the severe cases and the large number of infected patients in the epicentre, the national government immediately launched a number of measures, including the formation of specialized working groups, the mobilization of medical staff and medical facilities from neighbouring provinces to work in Wuhan, the construction of specialized hospitals etc. The Wuhan Red Cross and the provincial Red Cross, alongside another three organizations, were assigned to collect donations and organize the logistics of medical goods, but this came under fire due to a lack of transparency and inefficiencies. The nation then witnessed some harsh decisions, such as the removal of high-level officials in Hubei and Wuhan, and the investigation and reorganization of the local Red Cross.

Undoubtedly, the Chinese government’s determination and efforts to contain the spread of the epidemic are remarkable. It took as little as two weeks to build up a specialized hospital and as fast as one month to detect and settle the severely infected and mildly infected cases out of Wuhan’s five million residents. However, admittedly, the first two weeks after the city’s lockdown witnessed fear, panic and even deaths. A lot of requests for help can be found in Weibo, China’s twitter, and in WeChat feeds and WeChat groups. A professional media group analyzed the background of the help-seekers by applying big data. Overall they found 1183 help-seeking posts on Weibo2. 42.5% of those asking for help were elderly people aged 65 and above. The most frequent hashtags were “hospital”, “infection”, “hospital bed vancancies”, “doctors” and ”quarantine”.

In this critical period, the ordinary people of China immediately stepped up and joined forces to create informal online support networks to take care of emergency needs unmet by an overwhelmed government. One NGO leader, Mr. Hao Nan (郝南), the founder of the ZhuoMing Disaster Information Service, organized a group of volunteers to collect appeals for help from social media. Based on their analysis and after consultation with licensed doctors, Mr. Hao, who has a post-disaster recovery management background and is also a licensed dentist, initiated an online clinic with nearly one hundred doctors to provide tele-visits to people asking for medical advice.

Another group of volunteers gathered by Mr. Hao, labelled the “Little Angels”, were tasked with outreaching help-seekers by regularly viewing social media posts, mostly through Weibo, Douban, and WeChat moments referrals. The initiative was named the nCoV-relief Network, and later renamed the NCP Network. Soon enough, the online clinic’s volunteers realized that oxygenerators were the key to keeping the symptoms of infected residents from becoming very severe while they were waiting to gain admission to a hospital. This piece of information was shared with Hao’s NGO network, and a few more civic organizations and individuals joined together to gather donations, find sources of oxygenerator supplies and arrange logistics3. In less than one month, over 3000 oxygenerators were delivered to infected people in Hubei through a quickly established and civically-initiated chain of online supply.

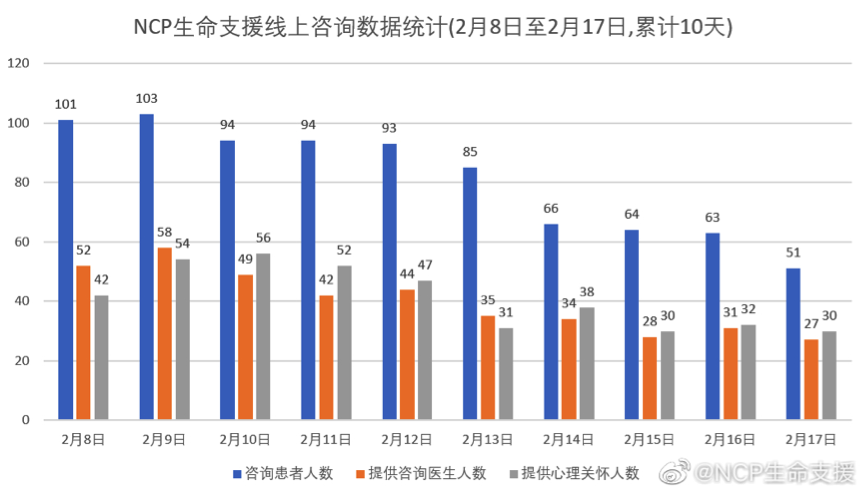

The special needs of pregnant women were also raised in the online clinic, resulting in a specialized online support group which included gynaecologists and pregnant women from Hubei. To address the mental health of infected residents as well as that of their families, an online caring group consisting of licensed social workers and psychologists was formed to provide psychosocial support. Statistics from the NCP network’s official Weibo shows that, as an informal online network, it was able to address an average of 200 requests daily from February 8 to 13, after which the government-initiated measures started to kick in, ensuring that more infected residents could receive treatment.

The graph above shows the figures for the NPC Network from the 8th to the 17th of February. The blue column shows the number of people who contacted the network to receive help, the orange column shows the number of volunteers providing medical advice, and the grey column shows the number of volunteers providing psychological support.

No theories can deconstruct the rationale behind the system’s efficiency; the volunteers’ strong motivation to help the needy and their dedication to tackle every barrier along the way outweighs all else. Needless to say, the professional nature of the assessments led to an efficient provision of help and to trust between the volunteers, NGOs and the private sector actors involved, setting up a basis for the smooth and efficient functioning of the helping chain. The majority of the volunteers are professional helpers, namely specialized doctors, experienced nurses and licensed social workers and psychologists. Their professional training and frontline work experience guarantees that they can assess the help seekers’ needs in a professional manner so as to offer tailored interventions. During the shortage of medical facilities and human resources in the initial two weeks, the online clinics represented hope for the vulnerable help-seekers of Wuhan.

At the organizational level we can see a bottom-up and decentralized approach. The efficient coordination between help providers, donors and suppliers can be attributed to the united determination to save lives. Once a question popped up, regardless of whether it was related to cash flows, the medical suppliers or logistics, it was immediately shared amongst NGO networks, alumni networks, self-support groups and private circles4. All such networks exhibited a strong foundation of trust amongst their members, allowing them to voluntarily address any issues that came up. The trust between the actors in play was a precious resource, something which the government was begging for.

Reviewing this supply chain of online aid, it is clear that social media served as a tool to connect various parties at a distance. Beyond their simple function as a communication tool, social media apps such as WeChat’s group video calls were used for online medical check-ups, and patients and their families could attend group therapy through Alipay’s DingDing Talk. This can be attributed to the ubiquity of China’s social media and the nation’s strong development of digital infrastructure.

Since it got easier for infected residents to receive treatment in mid-February, the role of the NCP and similar networks is now fading. The task for the future is perhaps to strengthen psychosocial support networks that can address the residents’ traumas. Psychosocial support requires a systematic and long-term plan and can hardly be achieved through volunteers alone. The future of the NCP and other such initiatives is unclear, but they have been of huge help for corovavirus-affected communities during the challenging initial stages of the outbreak.

As new cases of this potentially dangerous virus break out in other countries around the world, China’s online volunteer support groups could serve as a reference for affected communities globally.