Ryan Etzcorn currently lives in Beijing and works as a Program Associate for the Ford Foundation’s representative office there. He conducted the research used in this article as a 2018-2019 Fulbright Research Fellow. The views expressed in this article are entirely his own.

2016 was a big year. For almost every organization that claims a “social” mission in mainland China, that year and the two years leading up to it saw major structural changes. For most international observers, the marquee moment came with the passage of two laws of historic significance: the Overseas NGO Law and the more domestically focused Charity Law in late 2016. But even before that, new dimensions in China’s own domestic charitable and public welfare “ecosystem” were taking shape that have only intensified since – changes that have largely gone ignored by the international community.

While international institutions debate the Overseas NGO Law and struggle to cope with its changes, domestic Chinese voices have increasingly focused on dramatic challenges and opportunities rising in their own domestic sector. As foreign funds dry up and local forces mature and innovate in China, domestic organizations with a social mission still struggle to assemble the capacity needed to expand.

In this era of the new normal, how can small grassroots organizations link up with the financial and professional support they desperately need to survive and grow? In most societies, resources are often concentrated in the largest government and commercial institutions that struggle to form direct connections on the ground, which may be especially true for China. How can tiny community organizations dream of tapping into those resources in the hope of addressing issues like an aging population, incurable disease, acute disaster relief, or poverty?

Enter China’s quickly growing class of “platform” organizations. Sometimes called “intermediary” or “capacity building” organizations in the West, these organizations often work as magnetic hubs not just for the nonprofit sector, but across government, private, and community institutions. Their growth, especially in China’s large coastal regions, has been so prolific in the last few years that nationwide efforts such as the Narada Foundation’s Good Public Welfare Platform (Hao Gongyi Pingtai) and the digitally focused NGO 2.0 have even been established to focus collaboration even further.

So, what is a platform organization?

Platform organizations can perhaps be most simply defined by who they serve. Rather than providing direct services to communities of individuals on the ground, these organizations instead function to build up grassroots groups and help them sustain themselves. In short – they work like the central spine around which struggling community organizations can cluster when they need help and mutual support.

In nonprofit sectors with longer histories, these platform or “intermediary” organizations tend to share a few key functions, which can be summarized in three words: capacity, linking, and legitimacy. Platform organizations build skills that young organizations critically need, they create networks between organizations and sectors, and they also create transparency and offer insights into the complex and sometimes confusing field of social impact. Cutting across all three of these functions, however, is one of the stickiest problems for China’s relatively young nonprofit sector: funding.

Platform organizations in China typically take the form of associations, foundations, incubators, or institutes that provide knowledge or critical training needed to, for example, get your organization registered, lead you to new ideas for funding, or simply give organizations a space to convene and learn from each other. Arguably more significant is the fact that these organizations are increasingly shouldering responsibility for receiving funds from top-level government and commercial institutions and making judgments about how they are redirected at the grassroots level. It is this role that deserves special attention as a stampede of platform organizations arrive in Chinese society, often with different visions and financial backers. Without these middle institutions, even government agencies and wealthy donors with the best intentions find themselves parachuting relief downward with a thick fog separating them from the ground below.

Throughout 2017 and early 2018, I traveled back and forth between two southern Chinese cities, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, interviewing leaders in platform organizations, former government officials, and grassroots groups to find out how platforms were changing the game in China’s nonprofit sector.[1] Both cities are commercial powerhouses in Guangdong Province, and have long led the development of China’s nonprofit sector in several significant ways, but their characteristics and approaches to building a future for public welfare often differed.

Along the way, I asked questions that aimed to understand why platforms were growing in the first place, which platforms were rising in these two cities and how they were changing the rest of the nonprofit ecosystem. No matter who I talked to, a common theme across platforms with all different backgrounds was the government’s call, starting at the 19th Party Congress for “co-construction, co-sharing, and co-governance.”[2] Taken in the context of public welfare, I witnessed this phrase being echoed by community foundations, hub-style social organizations, and other intermediary organizations even while it was used to support slightly diverging visions for cross-sector collaboration in China’s future. Platform organizations of all stripes see themselves as a meeting place for the different strengths that private enterprise, government, and nonprofit organizations can all bring to the table.

Supply or demand – where are the platforms coming from?

It is no secret that the domestic nonprofit sector in China needs help if it wants to grow, and both government and social forces have made their own moves to address it. So, what’s holding nonprofits back? Ask almost anyone working in or with the sector and they will almost always list “professionalization” near the top of the list. Recent studies reveal that the sector continues to heavily employ young workers in their 20s and that turnover is rampant.[3]

But since recruitment is often left to the market, the lack of top talent always circles back around to one cold fact: professionalism chases the payday. It’s hard to attract top talent without competitive compensation and that classic problem has long plagued nonprofit sectors in western countries too, but the pay gaps in China have been even more stark. In 2018, the average annual salary of an employee in a Shenzhen nonprofit organization was 51,096 RMB ($7,514 USD) and secretaries at the very top of staff hierarchy only made an average of 17,500 RMB ($2,573 USD) per month, according to official statistics.[4] In one of China’s most expensive cities, that means it will be a struggle to pay rent, let alone support a family. Down the tracks in Guangzhou, the paychecks are even lighter. Platform organizations help mend this talent gap by providing free or subsidized training to organizations that cannot afford legal counsel, professional auditing services, or other kinds of critical know-how.

If the real core problem that most local nonprofits face is financial sustainability, then many see platforms as the new hope to boost what is often termed zi zao xue, or building “bone marrow” that self-generates financial “blood” for the organization in the future. Platforms can coach small grassroots groups on the latest online and offline revenue strategies. Using the term “resource docking” most platforms share a desire to see nonprofit organizations become more advanced in the ways they raise funds. They also tend to share a constant drumbeat for diversifying revenue through social enterprise, online fundraising, government programs, and other innovative means.

In the past decade, platform organizations have taken off, reshaping the social sector in the world’s second largest economy. Investigating the current expanding state of platform organizations in Guangzhou and Shenzhen quickly sheds light on how crucial they have become to convening voices across the world of social impact, whether in real time or online. Beyond just adding their own dimension, their presence sends a ripple effect throughout Chinese society by concentrating the influence of social forces, even as their numbers grow. One nationwide study found that since that year, the number of “support style” social organizations had risen by as much as 87% by 2018.[5] Despite that growth, platforms in the Pearl River Delta can still be distinguished by one key factor: who they answer to.

Administering a sector: the official path

As early as 2004, the Beijing and Shanghai governments were already experimenting with policy prescriptions to build “hub” organizations and community foundations that could act as a “bridge and belt” for a new era in “social governance” where private enterprise, government, and social organizations all worked toward common goals.[6] Startup platform organizations like Shanghai’s NPI teamed up with local governments to establish a system of incubators that could propel the city’s social organizations into a new era. Shenzhen and Guangzhou followed closely behind.[7]

Comparing both Guangzhou and Shenzhen reveals major differences in resources, culture, and other social elements, but those differences only make the fundamental similarities stand out more. The official model of government support for the sector follows a similar “supply-side reform” logic commonly found in China’s economy. Led by the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MoCA) in each city, this system combines the work of social organization “hub” organizations, incubator bases, charity federations, and think tank-style “institutes.” Although staff in these platforms are not technically government officials, they often work in coordination with each other and under direction of the relevant offices inside the city-level MoCA and mostly rely on State sources of revenue.

Differences between these two cities occasionally emerge and illustrate larger patterns in the way the social sector is treated in each city overall. In Guangzhou, for instance, the city MoCA established 45 incubator bases at city, district, and street-level with specific guidelines for how they can be incentivized through government subsidies pooled in a special, city wide fund.[8] Guangzhou platform leaders claim a more “systemic” environment of capacity support for nonprofits than Shenzhen, but the institutional map in Shenzhen still bears unmistakable similarities and benefits from being situated in an overall wealthier city.

These government platforms have established themselves as rare oases in what can otherwise feel like a vast funding desert for most civil society groups. But aside from just offering funding, they sometimes also offer a degree of oversight and legitimacy that nonprofits critically need in a sector that continues to witness scandals and experience social mistrust.

When Chinese social organizations use these platforms as channels to State resources, they sometimes report a particular challenge known as “mission drift” or “mission creep.” Only nonprofits that mirror government goals – such as poverty relief, education, or services for the disabled – have a chance of accessing the relief of State-affiliated funding lifelines. In some cases, they may even increase reliance on government contracts and other government handouts, which causes their central mission to “drift” in the direction dictated by shifting government mandates.

Society takes on more responsibility: new platforms after the Charity Law

While the Party-state has sought to shape a new era for Chinese civil society, new energy has also been developing around the edges of the official support system for China’s registered social organizations. An eclectic range of organizations have also established a presence in Guangzhou and Shenzhen with startup capital from wealthy community members, enterprises, or other non-government forces. These types of organizations most often include foundations, online donation platforms, and innovative consulting-style capacity building organizations, with plenty of blending between these different types.

Guangdong is home to more foundations (1,149 in 2019) than any other province in China.[9] The rise of private foundations founded and driven by enterprises exploded after 2008 when the limit on deductible income for enterprises for charitable donations rose from 3% to 12% in response to reforms made urgent by the Wenchuan Earthquake.[10] Enterprises have dominated giving in China ever since, but interviewees inside and outside government backed institutions often recognized that giving from these sources often exclusively follow government priorities.

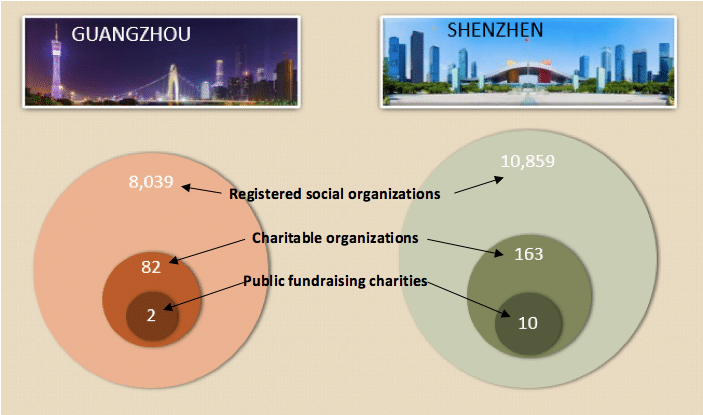

Now, a slowly growing number of foundations are beginning to gain official “public fundraising qualifications” as “Charitable Organizations” under the 2016 Charity Law, which grants them permission to serve as their own funding hubs both inside and beyond the confines of the city they reside in. Article 26 of the Charity Law has especially given these foundations the green light to fundraise on behalf of any organization without such qualifications.

Across multiple interviews in both Shenzhen and Guangzhou, Article 26 marked a major departure in sustainable, domestic financing for Chinese civil society organizations. Since 2016, a growing number of these groups have reported “affiliating” with credentialed public fundraising charities, usually under the auspice of setting up a “special fund.” Although organizations have been doing this since before the Charity Law, the passage of the law wedged the practice out of legal grey area into the light of the legally permissible.

Organizations hanging their name under the shelter of a public fundraising charity are not the only ones that stand to benefit from such arrangements. The public fundraising charities themselves have discovered that the special funds, and the 3-5% “affiliation fees” that they tend to charge for the privilege of hosting special funds, have the potential to become a key revenue source.

Article 26 and other supporting regulations that have followed have also paved the way for one of China’s most important developments in the charitable sector: the growth of online donation platforms. Now that small grassroots groups can openly pin their programs to public fundraising charities, they are qualified to raise funds through popular fundraising platforms offered by private sector giants Alibaba and Tencent and by large-scale events. 2018 marked the first time that these online fundraising platforms chose to intentionally slow down and direct more scrutiny at the organizations whose fundraising efforts they were hosting.

Despite these gains, the road ahead for China’s foundations remains uncertain. Outside of Shenzhen and Shanghai, city or community-level foundations hardly exist and foundations still make up only 0.8% of total registered social organizations in China.[11] In 2018, new draft regulations on the registration of social organizations may have cut off foundation registration below the provincial level and have put the minimum endowment size out of reach for many.[12] As recently as July 5, 2019, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued a warning to foundations that were “affiliating without managing” (gua er bu guan) their special fund programs, hinting that there may be less leniency for organizations that effectively rent out their public fundraising privileges with minimal fiduciary and political oversight.[13]

The slow growth of support platforms with social (rather than State) roots is producing a noticeable effect. Interviewees from both cities that worked with State-backed institutions admitted that new players in the world of charity and public welfare were creating new competition to attract donors, which in turn was forcing older, state-backed charities to “wake up” and reform. As several pointed out, this can lead to the positive by-product of traditional charity leaders, like the city Charity Federation, to modernize and professionalize the way they link donors to social organizations.

But if new layers of support are arriving for China’s nonprofits, is the sector on the verge of witnessing a new revival? Many grassroots groups remain skeptical, and in some cases, intermediary organizations can contribute to the problem. As government contracts out evaluation and training services for nonprofits, many of the smallest organizations are witnessing an explosion of administrative work.

For example, Organization A is based in a government-sponsored incubator that is run by an operating contractor (also a nonprofit). They receive training from a consulting “platform” style organization and liaison with a public fundraising foundation to launch a funding drive on TenCent Foundation’s “Lejuan” platform. They also receive government contracts that are evaluated by a third-party organization that is contracted by the government in turn. Organization A now faces a daunting mountain of monitoring and evaluation paperwork from six different organizations, including the government. Legal and financial reporting burdens for nonprofits remain far more intense than for organizations registered as businesses and it always seems like new pastures bring new paperwork.

A new era of resource diversity?

In many ways, it is still too early to tell, but many leaders in the Pear River Delta’s energetic nonprofit sector feel that the gradual expansion of fundraising options is still a good thing for the survival of the sector, even as foreign sources of funding are being phased out and running in so many different directions makes it hard to be efficient. Certain politically charged issue areas also remain sensitive, but for the vast majority of organizations focusing on education, environmental sustainability, eldercare, and other relatively benign issues, many social organizations are redoubling efforts to find money in new corners of society.

Whereas foreign actors in China frequently deploy a political lens centered on expression, many of China’s seekers for social justice and compassion have adopted a more dialectical and pragmatic approach when shaping the future of how the Party, government, society, and business might collaborate in the future to optimize services. Whether figures are closely attached to government or they stress rootedness in communities, the overwhelming majority of industry insiders I spoke with agreed that platforms were the future of cross sector collaboration and sustainable, diversified revenue streams. The question going forward will be, which platforms will stake out the most space in the sector?

In both the West and in China, platforms still face a few key challenges. The first is their struggle to stay visible in their communities. After all, if they do not directly provide services to the people, how do they ever establish any brand awareness? This key vulnerability creates another problem, that platforms are occasionally viewed as proxies of a few, large-scale donors. As one interviewee put it, borrowing from Chinese traditional culture, platform organizations often act like a subservient “daughter-in-law” (xifu) for the government, a wealthy family, or a trade association. Another interviewee remarked that “every platform has a sugar daddy.” Ironically, the very platforms that grow the capacity of grassroots organizations to establish their independence by diversifying revenue sources usually depend on one or two main revenue sources themselves. In the end, they struggle to practice what they preach.

In spite of the challenges, the efforts of China’s organizations in the middle – whether incubators, institutes, foundations, or hub associations – look like they may be paying off. A June 2019 report found that professionalism in the nonprofit sector is on the rise, attributing much of the gains to increased participation in training and capacity building, especially among nonprofit leaders.[14]

Training and other forms of in-kind donations are important to capacity building, but the most important new shift may be that organizations are finding in the process of increasing their sophistication is that platform organizations are guiding much of the sector to new forms of sustainable fundraising. Young nonprofit employees are attending seminars and workshops throughout China on how to reach new donors through new media, apply to grants from foundations, and bring in more government contracts. Whatever the funding source, it has become increasingly clear in China that nonprofits will need every kind of resource they can get to heed the government’s call to take on a more active role for collaborative social governance. Now on the rise, platform organizations are the new unavoidable meeting places for government, nonprofits, and enterprise as they struggle into a new era together.

[1] 46 interviews were conducted in all, with 22 being conducted with representatives of Guangzhou-based organizations and 24 being conducted with Shenzhen-based organizations.

[2] http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-03/15/content_5373799.htm

[3] ABC, https://www.itopia365.org/news/Details/20

[4] Chen Deming, “Shenzhen Social Organization Talent Building Report”, Shenzhen Social Organization Development Report, 2018.

[5] Qiu Zhonghui, She Hongyu & Chen Fahua, Conceptual Fundamentals of Support-style Social Organizations, Blue Book, 2019.

[6] Beijing Municipal Ministry of Civil Affairs, “Opinion on accelerating the promotion of social organization reform and development”, 2008.

[7] http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2010-07/06/content_1646850.htm

[8] Guangzhou Ministry of Civil Affairs, July 24, 2018, “Guangzhou Social Organization Cultivation and Development Base Management Measures.” https://www.gz.gov.cn/gzswjk/2.2.17.1/201807/59ba1ab12ef64f5abf 3589ac767ef124.shtml. This policy is an update on an earlier version that had been active since 2013.

[9] https://www.pishu.com.cn/skwx_ps/databasedetail?SiteID=14&contentId=10983341&contentType=litera ture&subLibID=

[10] Anke Schrader and Mingxia Zhang, “Corporate Philanthropy in China,” The Conference Board Report, 2012

[11] Data.chinanpo.gov.cn

[12] http://chinadevelopmentbrief.org/news/the-new-draft-on-the-registration-of-social-organisations-15-points-of-note/

[13] 民政部:基金会对外开展合作不得“挂而不管”、“顾而不问”, http://www.chinadevelopmentbrief.org.cn/news-23018.html

[14] http://www.chinadevelopmentbrief.org.cn/news-22917.html