“It’s hard to describe how much I want to try a driverless car. It would be so cool because it could take me anywhere I wanted, without bothering anyone — driverless vehicles can really make life easier for us visually impaired,” wrote Xu Bishan from Zhanjiang Special Education School after attending a recent online education program for blind students.

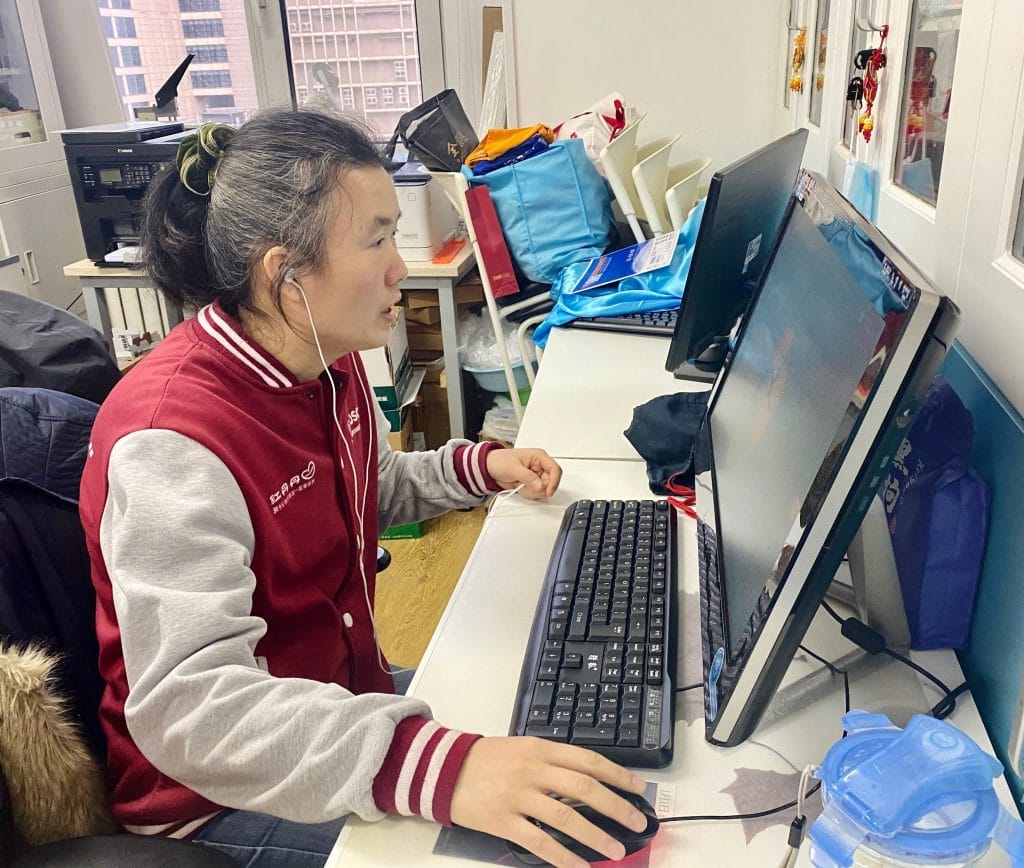

The program “e-seeing the world”, launched by Beijing Hongdandan Cultural Service Center for the Visually Impaired, provides online courses for blind students across China, according to Zeng Xin, Hongdandan’s executive director.

The first phase of the program runs from September to February, and the courses are livestreamed from places that are often difficult for visually impaired people to access. The topics are closely related to their daily lives. For example, the courses have covered the work of a TV crew and two tech companies – and will soon feature a livestream from a sewage treatment plant.

For each of the courses, Hongdandan sends a blind “touch experiencer”, a visual storyteller as well as some support staff for the broadcast. The touch experiencer usually starts by touching as many things on site as possible and asking the experts questions from the perspective of a blind person.

The visual storyteller provides all the visual details to the students by describing everything — from what a driverless car looks like to what kind of radar the car uses.

“We want them to escape the limitations of the interactions built in to their daily routines and open their minds to learn about other aspects of the world, from cutting-edge technology, to history, culture and lifestyles,” Zeng told CDB in a recent interview.

“And by reaching out to find the right places for our courses, we are also making the blind community and our needs visible to more people.”

Diagnosed with severe amblyopia – often known as “lazy eye” — in elementary school, Zeng grew up trying to keep pace with her peers. When she was a child, social integration was not possible, let alone courses or events specifically designed for the visually impaired.

A lack of job opportunities

Although she grew up suffering from poor vision, and was told by doctors that she’d go blind before turning 18, Zeng attended normal schools. She would sit in the front row, find a bright place to read, and use a magnifying glass when necessary.

After passing the college entrance examination, she had to take a medical exam for college enrolment. During the eye test, she had to ask her friend to stand behind her and secretly tell her the correct answers.

“If I took the eye test by myself, the university would not accept me,” Zeng explained, “because by Chinese standards I would be considered disabled and get a disability certificate, but with a disability certificate I’m not sure any of the ordinary universities would take me.”

“By the time I went to college in 1998, I hadn’t heard any cases of blind people taking the college entrance exam,” she said. “In my county or city, people barely knew about special education or what blind people could achieve after being educated.”

During the four years of university, only Zeng’s roommates knew about her vision problems — her teachers and classmates had no idea. But when she tried to get a job after graduation, she found it hard to keep up with the pace of office life.

“I was interviewed by several companies, and it all went pretty well at first — they didn’t really spot my eyesight problem, except that maybe I walked slowly,” Zeng said. “But once they knew about my vision, they would just turn me down before I’d signed a contract. I did manage to try a few jobs, but none of them lasted long, because the companies simply didn’t offer the support I needed.”

With her vision deteriorating and after an unsuccessful attempt at passing the postgraduate entrance exam, Zeng learnt the braille alphabet from scratch. But her career choices remained limited.

Racked with uncertainty about her future, she came across a radio program called “Heart Sees the World” partly produced by Hongdandan’s trainees — a group of blind youths.

“The idea that blind people could be radio program producers was really eye-opening for me,” Zeng said.

Hongdandan

Inspired by a TV program featuring the lives of people with disabilities she co-produced with China Educational Television, Zheng Xiaojie founded the Beijing Hongdandan Education and Cultural Exchange Center in 2003. She wanted to improve the employability of disabled people and help them become “active participants in society rather than charity recipients”.

Hongdandan started by teaching visually impaired youths to use their hearing to learn how to produce radio programs, which led to the airing of “Heart Sees the World” in May 2004.

Interested in Hongdandan’s mission to expand employment opportunities for people with disabilities, Zeng approached the organization, quickly becoming a full-time volunteer and taking over tasks such as project execution and management.

She says the first few years were difficult due to limited resources and funding — and all the full-time volunteers had to learn everything from scratch.

“At first I didn’t have a clue how to do the budgeting, and it took a lot of practise for us to learn how to draft project proposals.”

Zeng also took part in NGO capacity building sessions offered by other NGOs in Beijing in order to better prepare herself for running projects on behalf of Hongdandan.

Dedicated to serving the blind

There were not many NGOs or charities dedicated to helping the blind in China, and organizations providing cultural services were even rarer, said Zeng explaining why they decided to make blind and visually impaired people the center of Hongdandan’s work in 2006. The organization officially changed its name to Beijing Hongdandan Cultural Service Center for the Visually Impaired when it registered with Beijing Civil Affairs Bureau as an NGO in 2013.

“Even today, the number of organizations dedicated to serving the blind remains tiny,” Zeng told CDB. “So for us, it’s vital to focus on the diverse needs of the blind community and strive to cover the things they need throughout their lives.”

Training visually impaired youths how to collect information, edit clips and broadcast live through the Heart Sees the World program taught them an important lesson: in order to improve trainees’ output on air, more visual information needed to be made available to them beforehand.

“When training blind youths to become broadcast journalists, we realized that they can be relatively monotonous when describing things. It may be easy for them to prepare for one on-air program, but if they need to keep on doing 10 programs, they struggle — not because they don’t work hard enough, it’s simply down to the fact that they can’t see,” Zeng explained. “They lack understanding of the outside world due to not having visual references, which limits what they are able to tell the audience on air.”

In order to fill the information gap, they came up with the “Heart Cinema” program, which shows movies to a visually impaired audience. During each screening, professionally trained volunteer narrators describe the scenes, helping those with visual impairments appreciate the film without interfering with the movie dialogue.

Starting with narrated movie screenings specifically for Hongdandan’s radio program trainees in 2005, the program soon started to pick up an audience and in less than a year, it had become a regular event for blind audiences.

“Heart Cinema has been our signature program for quite some time, and we intend to keep running it for as long as we can.”

To read part two of this interview click here.