This is an article put together by China House, discussing a project they have undertaken to fight against FGM in Kenya.

Angela, a Maasai woman in her fifties, lives in an eastern Kenya township with the tradition of practicing FGM (female genital mutilation). Because of her education and Christian beliefs, Angela changed her attitude towards circumcision. When her mother-in-law insisted on circumcising Angela’s daughter, she calmly said: “I’ll do it myself.” Then Angela took her daughter out and never did it.

Today Angela has become an activist fighting for women’s rights as the cofounder of the Maasai Girls Life-Time-Dream Foundation in Oloitoktok. The organization has collaborated with a Chinese organization since 2017 to help rescue girls from FGM, early marriage and lack of education.

The Fight Against FGM is Still Going on Today

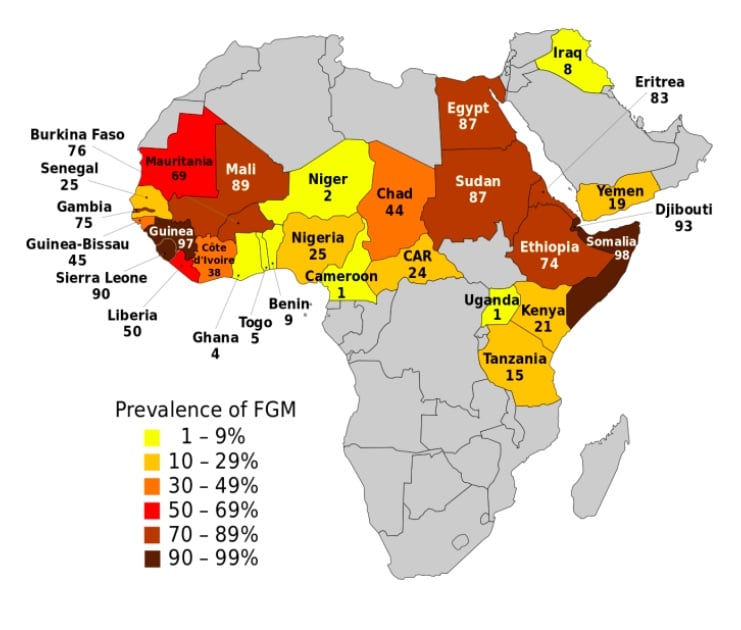

FGM is the ritual removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. Today it is widely present in areas such as South Asia, the Middle East, and some parts of America, but it is most concentrated in Africa. As estimated by the World Health Organization, 3 million females will undergo circumcision each year.1 That is one girl circumcised every 8 seconds.2

Figure 1: Prevalence of FGM in Africa

Among all African countries, Somalia has the highest prevalence of FGM (98%).3 In Kenya, Somali, Maasai and Samburu are three tribes with relatively greater percentages of implementation. In Maasai culture, FGM is performed for the purpose of religious belief, as well as to prevent fornication. Most importantly, this tradition is believed to be the shifting point when a young girl finally becomes a grown woman, and the implementer is the most direct contributor.

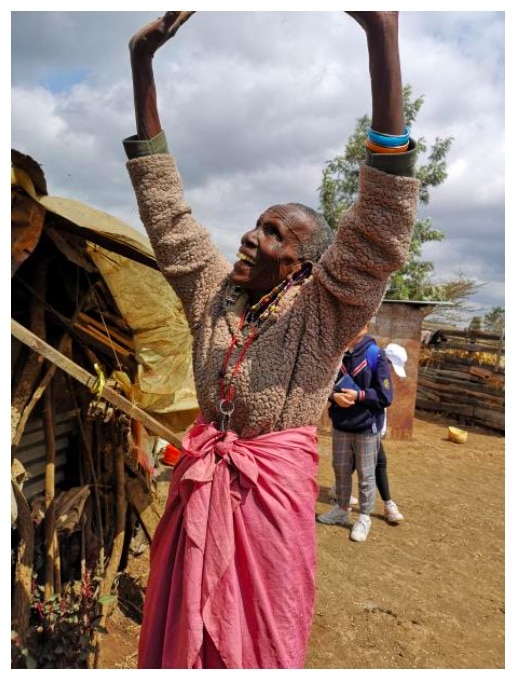

One of the old implementers in a Maasai village, Nkoije Parsale, explained her impression of circumcision: “I did not do the job for money, I did it for honor and pride; the villagers respected me greatly.”

Back then, people believed that circumcision is a big festival: families would cut a big stick (tree) and kill bulls to show the neighborhood that something celebratory has happened in the house. The mental and physical damages brought to the girl by circumcision itself were never considered; instead the community emphasized it as a point of pride.

Figure 2: a Maasai women who used to be an implementer of FGM, welcomes and greets us with the traditional gesture.

Although the Kenyan government has passed laws to prohibit circumcision, this old tradition is still prevalent and secretly implemented.

A Maasai survivor (a girl who is rescued from circumcision), Nashipai was tortured by her parents because of her refusal to undergo FGM. She escaped and ran barefoot for days to look for a shelter. Although Nashipai was later rescued, her mental counselor revealed, she lost all hope. She struggled to communicate with others because of the long-lasting mental effects brought by circumcision and the immense pressure from her family.

There are 79 NGOs (Non-Governmental Organization) working towards ending FGM in Africa. Most of them are funded by the western countries.4

In Kenya, the Girl Generation is a foundation sponsored by DFID (UK Department for International Development). They offer resources, financial support, and training sessions for poorly resourced grassroots organizations to fight against FGM. As the project manager explained: “We provide funds ranging from 50,000 to 100,000 USD per year to other local anti-FGM organizations in Kenya, and we are the only money-giving NGO in Kenya in this area.”

China is Finally Joining the Fight

In 2017, there was the first case of Chinese participation in addressing the issue of female genital mutilation in Africa. In the same year in July, China House led 14 Chinese teenagers to Oloitoktok, Kenya to research and explore the local culture of circumcision. They plan to construct a rescue center with accommodation, education, food, clothing, and other daily necessities for Maasai girls who are rescued by the local policies. Moreover, they are working towards a self-containing operational system: a cycle in which the center makes money by raising animals such as cows, sheep and chickens, as well as making and selling handicraft to China.

China House, founded in 2014, is a social enterprise to help the new generation of Chinese to integrate in to Africa via programs of research, internship, and volunteering services. As one of the pioneers contributing to Sino-African cooperation, China House aims to combine the social and financial development of the local communities with the current trends in China, where many teenagers are going abroad.

“The End FGM—Maasai Girls Rescue Program” is one of China House’s programs in Kenya, and Ziqi Ai is the project manager. According to Ai, she met the founder of the Maasai Girls Life-Time-Dream Foundation, Soila, in 2016.

In the past, Soila and her team used their own savings to provide financial support for the rescued girls. When the number of Maasai girls who needs protection from FGM rose, Soila decided to collaborate with China House to create a more formal and sustainable NGO.

Figure 3: Chinese Students at the Maasai Girls Life-Time-Dream Foundation

China House uses this program to teach Chinese students how to do research and community projects and collect tuition fees from them. Out of such fees, a portion will go directly to the project. At the same time, under assistance and instruction, the Chinese students would try to raise more funds through donation activities and business strategies.

“As a social enterprise, we hope we can reach an ideal mode of win-win: the Maasai Girls Life-Time-Dream Foundation will receive funds from China, the Chinese students gain experiences, and China House obtains profits to achieve continuous and progressive development,” Ai explained.

How the New Model of China-Africa Relations Can Emerge From the Obstacles

Unlike western aid in Africa, which has developed for a long time, Chinese have just begun to learn how to conduct development projects in Africa.

Seeking funds from China is challenging, as China does not have a system of supporting NGOs, both regarding the financial system and the culture.

“It is hard to get money in China, and if we get money from the west we would be suspected by Chinese people; most Chinese people have an understanding that NGOs should not charge for anything, and people in NGOs are volunteers who should not be paid or should be paid minimally,” says Hongxiang Huang, founder of China House, explaining why China House uses a social enterprise model instead of an NGO model.

Local implementation has given Ai a headache as well.

“We rented a house and paid the landlord to furnish it, but the landlord delayed for months and used the money for his new phone,” Ai says recalling the unexpected difficulty in building a rescue center.

And finally when a rescue center was ready to be used in 2018, the local government had a policy change and the rescued girls have not been permitted to live in that place until now.

“It was not as successful as it should be, but at least the funds we raised are supporting some rescued girls to get food, clothing and go to school,” Ai says.

While the project has some impact on local communities, it seems like it has impacted the participants as well —- the Chinese students who participated in this program.

“I was influenced by the locals’ hospitality, and I gradually found it easier to engage with people who speaks other languages and from other cultures,” said Pengyi Chen who participated two years in a row.

A Seeding Can Grow

Eight miles from the Maasai Girls Life-Time-Dream Foundation in Oloitoktok, is another rescue center sponsored by a British family. The Divinity Foundation International has been running for ten years, and it is a complete and mature system operating with sufficient infrastructure, experienced employees, and sustaining funds; its existence has become more influential to the local community with every passing year.

When the project manager Daniel was asked to comment on the center’s evolution, he said: “the whole process was like a journey. We sure struggled at first, but as the years pass by, we grow stronger and stronger. I can see the improvements.”

Notes:

1. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation

3. https://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGMC_2016_brochure_final_UNICEF_SPREAD.pdf