Editor’s Note

This article was originally produced by the Center for Charity Law of the China Philanthropy Research Institute at Beijing Normal University. For the original version, please see here.

【Intro】The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of the Activities of Overseas Nongovernmental Organizations in the Mainland of China” (hereinafter referred to as the ONGO Law) was promulgated on April 28, 2016 and officially came into effect on January 1 2017. Since January, the number of representative offices (RO) of ONGOs successfully registered has been slowly increasing. By the end of May, the total number of registered ROs in China stood at 99. The number of temporary activities recorded by ONGOs was 76. From the law’s promulgation to its implementation , the Ministry of Public Security and provincial public security organs conducted preparation and implementation work.

At the end of 2016, the Ministry of Public Security issued the “Guide for the Registration of Representative Offices and Submitting Documents for the Recording of Temporary Activities of Overseas Nongovernmental Organizations” (hereinafter referred to as the Guide), and the “Catalogue of Fields and Projects for ONGOs with Activities in China, and Directory of Organizations in Charge of Operations (2017)” (hereinafter referred to as the Catalogue). The MPS has also coordinated supervision and management efforts and launched the online ONGOs’ service platform. Most provincial public security organs have also published local catalogues of program fields and projects for ONGOs, and local directories for potential Professional Supervisory Units (PSUs).

At the end of 2016, the Ministry of Public Security issued the “Guide for the Registration of Representative Offices and Submitting Documents for the Recording of Temporary Activities of Overseas Nongovernmental Organizations” (hereinafter referred to as the Guide), and the “Catalogue of Fields and Projects for ONGOs with Activities in China, and Directory of Organizations in Charge of Operations (2017)” (hereinafter referred to as the Catalogue). The MPS has also coordinated supervision and management efforts and launched the online ONGOs’ service platform. Most provincial public security organs have also published local catalogues of program fields and projects for ONGOs, and local directories for potential Professional Supervisory Units (PSUs).

Fig.1 Number of Registered ONGOs in 2017 (January – May)

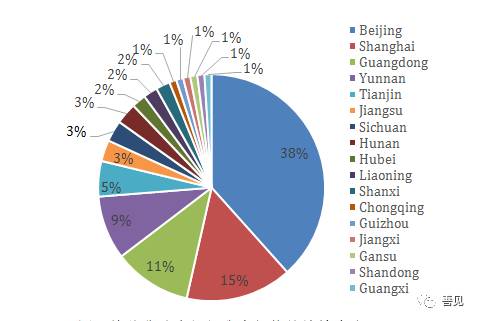

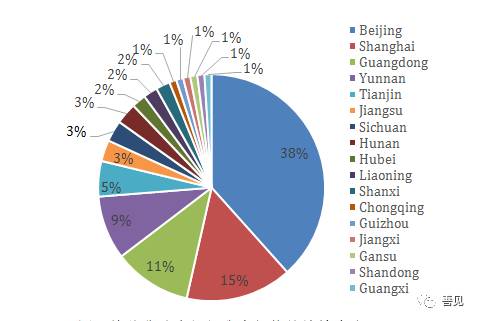

In terms of geographical distribution, as shown in Fig. 2, the 99 ROs registered so far are located in 17 provincial-level areas (including autonomous regions and municipalities). Most of these ROs are located in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Yunnan and Tianjin. The number of ROs registered in these five provinces accounts for 78% of the all the ROs around China. Besides, there have also been ROs registered in Jiangsu, Sichuan, Hunan, Hubei, Liaoning, Shaanxi, Chongqing, Guizhou, Jiangxi, Gansu, Shandong and Guangxi. So far, 38 ROs have been registered in Beijing, making Beijing the provincial area that has the highest number of ROs (38% of the total number). The numbers of ROs in Shanghai, Guangdong, Yunnan and Tianjin are respectively 15, 11, 9 and 5, which accounts for 15%, 11%, 9% and 5% of the total number, respectively.

Fig.2 The Geographic Distribution of ROs

On the other hand, the fields of the ONGOs’ projects have expanded as the number of registered ROs increases. In accordance with how the Catalogue defines the fields of ROs’ projects, we discovered that the ROs registered in the first three months of 2017 work in five different fields—economy, poverty alleviation and disaster relief, health, environmental protection and education. Two new fields– culture and sport, can be added due to the ROs newly registered in April and May. Based on the current registrations, most of the ROs mainly conduct projects in the economic field. Their work scope includes trade, investment and cooperation, market research, business liaison for agricultural products and technological exchange. In the meantime, there are many organizations that work in the poverty alleviation & disaster relief and health fields. The themes of the projects in the poverty alleviation & disaster relief fields include poverty-aid, elderly services, disaster prevention and relief and social organizations development promotion. There have also been a few ROs that work in other fields, including environmental protection, education, culture and sport.

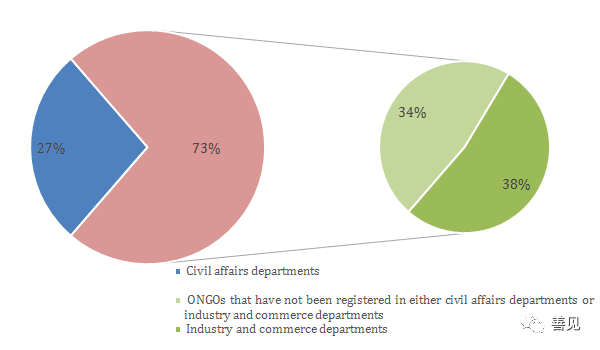

Before the promulgation of the ONGO Law, there was no systematic management for ONGOs that conducted activities in Mainland China. There were various formats of registration—some were registered under civil affairs departments, some under industry and commerce departments, and others conducted their activities using other legal entities or never got registered. As is shown in Fig. 3, out of the 99 ROs registered after the promulgation of the ONGO Law up to May, 27 (27%) of them were once registered under civil affairs departments. These ROs were handed over to public security departments after the promulgation of the Law.

Among the other ROs, 38 (38%) were once registered under industry and commerce departments. Besides, there were 34 (34%) ROs that conducted their activities in other forms or never got registered at all, and they did not possess the status of legal persons before the promulgation of the ONGO Law. In fact, except for those ROs that were once registered under civil affairs departments, it was after the promulgation of the ONGO Law that the other two types of ROs obtained legal status to conduct non-profit activities in Mainland China. So far, out of the ROs registered after the ONGO Law came into effect, 73% can thus be considered newly registered non-profits. This shows that the implementation of the ONGO Law has helped more ONGOs obtain legal status to conduct non-profit activities in Mainland China.

Fig. 3 The Distribution of ONGOs Previously Registered[3]

Source: public information

In terms of the geographic distribution of “previously registered ROs”, the 27 ROs that were once registered under civil affairs departments have now been handed over to different provincial public security departments. 22 of them were handed over to the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau; two were handed over to the Guangdong bureau; two to the Shanghai bureau and one to the Jiangsu bureau.

The distribution of the 38 ROs that were previously registered under the industry and commerce departments is: 13 in Shanghai, ten in Beijing, five in Guangdong, two in Jiangsu, two in Hubei, and one in each of the following provinces—Gansu, Hunan, Tianjin, Sichuan, Yunnan, Chongqing.

There were 34 ROs that were neither registered under civil affairs departments nor under industry and commerce departments. Eight of them are now registered in Yunnan, six in Beijing, four each in Guangdong and Tianjin, two each in Hunan, Liaoning, Sichuan and Shaanxi, and one each in Jiangxi, Shandong, Guizhou and Guangxi. The geographic distributions of these ROs are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig 4. The Geographic Distribution of Newly Registered ROs

Currently Beijing has 38 registered ROs, becoming the provincial region with the highest number of registered ROs. 22 of them are ROs of overseas foundations that were previously registered under the civil affairs departments. Since the required procedures to transfer these ROs over to the public security departments are relatively simple, most of these ROs successfully completed their registration process in January.

Another ten ROs in Beijing used to be registered under industry and commerce departments and belong to chambers of commerce or trade associations, such as the Beijing Office of the US-China Business Council and the Beijing Office of the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers. These are non-profit organizations that engage in activities of “mutual benefit”, and in practice it is relatively easier for them to find PSUs.

It is noteworthy that there are another six public welfare organizations in Beijing which were never registered under either civil affairs departments or industry and commerce departments. These six organizations have obtained legal status because of the ONGO Law, including the Beijing Representative Office of the Nature Conservancy and the Beijing Representative Office of the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Foundation. These organizations successfully registered their ROs in May, and they account for 60% of all the registrations that were completed in that month. Out of the top three provincial areas that have the highest numbers of registered ROs, Beijing has more newly registered ROs of non-profit organizations compared to Shanghai and Guangdong.

So far, the nine ROs registered in Yunnan Province all belong to charity-focused (rather than trade-focused) NGOs. They were all successfully registered in April. In December 2009, Yunnan published the Notice on Publishing Provisional Regulations of ONGOs’ Activities, demonstrating that the province has made its own efforts in establishing a system to regulate ONGOs. We found that out of the nine ROs registered in Yunnan, eight used to be registered under the Yunnan’s Ministry of Civil Affairs. Although the registration system established by Yunnan Province cannot be equated to the current official registration system in terms of legal validity, the previous registration records have helped facilitate the registration of ONGOs in Yunnan.

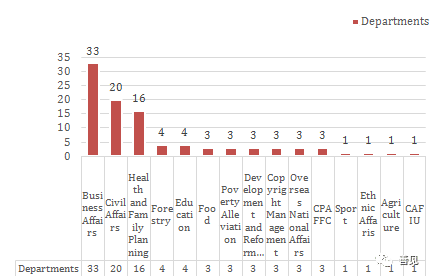

When an ONGO registers its RO, it needs to submit an application to its PSU, specifying the scope of its work, the region of its activities and the need for it to conduct certain activities. After receiving permission from the PSU, it can then submit a request to the public security departments to establish an RO. Therefore, it is very important for an ONGO to find a proper PSU in order to register its RO successfully. As shown in Fig. 5, the commerce departments are in charge of the largest number (33) of ROs, making this department the most common PSU. The ROs under their charge mainly work in the economic field. The civil affairs departments and health and planning commissions are respectively the second and the third on the list. The former is in charge of 22 ROs that mainly work on helping the poor and disaster relief. The latter is in charge of 16 ROs that mainly work on medical treatment and health-related issues.

The forestry departments and educational departments are each in charge of four ROs. The food departments, anti-poverty departments, the Development and Reform Commission, copyright management departments, overseas nationals affairs departments and the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) are each in charge of three ROs. The sports departments, ethnic affairs departments, agriculture departments and the China Association for International Understanding (CAFIU)are each in charge of one RO. From the data, we see that commerce departments, civil affairs departments and health and family planning commissions, who rank top three in terms of numbers, are in charge of most of the ROs.

Fig. 5 Distribution of Professional Supervisory Units

Source: ONGO Service Platform

We have learned that it is harder for ONGOs to secure the National Health and Family Planning Commission as their PSU. Local health and family planning commissions, such as the Beijing and Shanghai commissions, are not very active in taking charge of new ROs. However, data shows that the health and family planning commissions still rank third among PSUs in terms of the number of ROs registered under them. This is because among the 16 ROs currently registered under the charge of the health and family planning commissions, six ROs were originally registered under the Ministry of Civil Affairs with the National Health and Family Planning Commission as their PSUs. Another six ROs were originally registered in Yunnan Province under the charge of the Yunnan Health and Family Planning Commission. This matches the fact that the ONGOs in Yunnan mainly work on the health issues there. Out of the other four ROs, two of them are in Sichuan and one each in Shandong and Gansu. Based on the geographic distribution of the ROs under the charge of civil affairs departments, we see that civil affairs departments in different regions have different levels of enthusiasm in terms of becoming PSUs. Many local civil affairs departments have become the PSUs for some new ROs, such as the RO of World Vision Hong Kong.

Among the 99 registered ROs, some of them actually belong to the same ONGOs. So far, there are seven ONGOs with multiple RO branches, totalling 18 ROs as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 ONGOs that set up multiple ROs

| No. | Name | ROs | Region of Activities |

| 1 | China-

Britain Business Council |

Nanjing

RO |

Jiangsu

Province |

| Changsha

RO |

Hunan

Province |

||

| 2 | World

Vision Hong Kong |

Guangdong

RO |

Guangdong

Province |

| Yunnan

RO |

Yunnan

Province |

||

| Guizhou

RO |

Guizhou

Province |

||

| Jiangxi

RO |

Jiangxi

Province |

||

| Tianjin

RO |

Tianjin City

(Municipality) |

||

| Guangxi

RO |

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region | ||

| 3 | U.S.

Soybean Export Council |

Beijing

RO |

Beijing,

Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Shandong, Henan, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Ningxia, Gansu, Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai |

| Shanghai

RO |

Shanghai, Jiangsu,

Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Hubei,Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan |

||

| 4 | MSI

Professional Services (Hong Kong) |

Sichuan

RO |

Guangdong,

Shaanxi,Anhui, Ningxia, Hubei, Shandong,Jiangxi, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, Guizhou, Jilin, Chongqing, Tianjin, Liaoning, Shanxi, Henan, Inner Mongolia, Hainan,Sichuan, Fujian, Gansu, Tibet, Guangxi, Jiangsu, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Hunan, Hebei, Beijing |

| Yunnan

RO |

Yunnan | ||

| 5 | Korea

International Trade Association |

Beijing

RO |

Ningxia,

Shandong, Jilin, Tianjin, Liaoning, Shanxi, Henan, Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Hebei, Beijing |

| Shanghai

RO |

Hubei, Jiangsu,

Hainan, Fujian, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Hunan, Guangdong, Anhui |

||

| 6 | US-China

Business Council |

Beijing

RO |

Beijing, Tianjin,

Hebei |

| Shanghai

RO |

Shanghai, Shanxi,

Inner Mongolia, Liaoning,Jilin Heilongjiang, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi,Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Xizang, Shanxi, Gansu, Qinhai, Ningxia, Xinjiang |

||

| 7 | Project

Hope (U.S.) |

Shanghai

RO |

Shanghai,

Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, Guangxi, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Qinghai, Xinjiang |

| Beijing

RO |

Beijing, Tianjin,

Hubei |

According to Article 18 of the ONGO Law, “Representative offices of overseas NGOs shall operate under their registered names when carrying out activities within their operational scope and area”. Therefore, ROs cannot conduct activities outside of their operational areas. However, according to the Guide, when an ONGO registers its operational area, it “shall specify its area of activity within the mainland of China, within or across a particular provincial administrative division, and the area of activity shall be in line with its scope of operations and the needs of its actual activity”. This is to say that the actual activities could take place beyond its registered operational area. Therefore, many ROs conduct activities beyond their registered operational areas.

However, we find that the attitude of the PSUs determines whether an RO could operate outside of its registered operational area. Currently, ROs whose PSUs are national-level ministries or commissions can generally have operational areas that stretch across multiple provinces or nationwide. Also, since activities in the business and commerce field are usually cross-regional, most ROs that are under the charge of the commerce departments also operate in multiple provincial regions. Most of the ROs that are under the charge of civil affairs departments only operate inside their registered operational area, but there are also a few exceptions—for example, the Chongqing office of the Australian Charitable Aid Service Company is under the charge of the Chongqing Civil Affairs Bureau, but it operates in Yunnan province as well as in Chongqing.

In practice, one of the main reasons why some ONGOs set up multiple ROs is because they cannot receive the endorsement of their PSUs to conduct cross-provincial activities. Therefore, in order to be legally qualified to do so, they can only register multiple ROs in the relevant regions, with multiple PSUs endorsing their local RO activities. Another reason that some ONGOs set up multiple ROs relates to their future development. According to the Guide, “in the case of an overseas NGO with two or more ROs, there shall be no overlapping of the specified locations of activity among its ROs”.

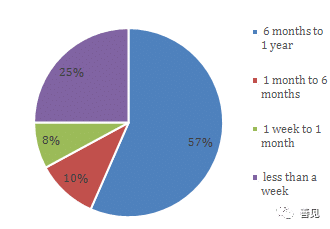

According to article 16 of the ONGO Law, “overseas NGOs that have not established representative offices but need to conduct temporary activities in the mainland of China shall do so in cooperation with state organs, people’s organizations, public institutions and social organizations (hereinafter referred to as “Chinese partners”)”. Up to the end of May, there have been 76 filings of ONGOs’ temporary activities. According to Article 17 of the ONGO Law, “the duration of temporary activities shall not exceed 1 (one) year”. As shown in Fig. 6, out of the 76 temporary activities, 43 of them have a duration from half a year to one year, accounting for 57% of all the 76 activities. 19 of them have a duration of less than a week, accounting for 25% of all the activities. Eight of them have a duration of a month to half a year, accounting for 10% of all the activities. And six of them have a duration from one week to one month, accounting for 8% of all the activities.

Fig.6 The distributions of ONGO’s temporary activities

Source:ONGO Service Platform

We see that the most common duration is from six months to one year, covering more than half of all temporary activities. This type of temporary activity is usually carried out in the form of research, high-performing team building and long-term projects. The fields of these activities include community support, support of the elderly, educational support, disaster prevention and relief, environment protection etc. The second most common type of temporary activities is those with a duration of less than a week. These activities are usually in the form of a conference or training session. The fields of these activities include technology, agriculture, health, education, etc.

After the promulgation of the ONGO Law, some people suggested that ONGOs having difficulty in registering their RO in a short period of time may turn to file their temporary activities as another way to obtain legal status. However, we find that those ONGOs who have not registered their ROs successfully have little tendency to apply to file for temporary activities. This is because the requirements for filing a temporary activity are similar to those for registering an RO. Other ONGOs may think that since the duration of a temporary activity shall not exceed one year, the cost of the preparation work is too high.

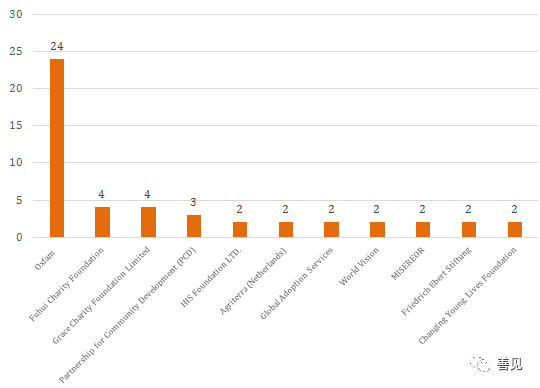

Looking at all the 76 filings of temporary activities, 11 ONGOs have two or more filed temporary activities each, for a total of 49 temporary activities, accounting for 64% of the total.

Fig.7 ONGOs that have two or more temporary activities

Source:ONGO Service Platform

Oxfam Hong Kong has the highest number (24) of temporary activities recorded, involving eight provincial regions including Guangdong, Guangxi, Gansu, Anhui, Sichuan, Qinghai, Shaanxi and Guizhou. The temporary activities of Oxfam Hong Kong account for 32% of all the temporary activities filed so far, with a number six times larger than the second NGO on the list, Fuhui Charity Foundation.

All in all, besides registering ROs, the filing of temporary activities offers another possibility to conduct non-profit activities. It meets the needs of two types of ONGOs: ONGOs that only need to hold temporary activities such as a conferences and do not plan to launch long-term projects in Mainland China; or ONGOs that have not yet completed the registration process of their ROs but would meanwhile like to carry out their work.

[1] The data in this report are obtainedfrom the ONGO Service Platform initiated by the Ministry of Public Security,the local ONGO service platforms and the information published by relevantorganizations by May 31.

[2] ”Fu Ying: ‘There have been more than 7000 ONGOs in China’”, Wangyi News,http://news.163.com/16/0304/12/BHAHFU9K00014AED.html,last access time:(5/19/2017).

[3] ONGOs that have not been registered in either civil affairs departments or industry and commerce departments account for 34.3%, and ONGOs that have been registered in industry and commerce departments account for 38.4%.

[4]The Information was collected from public resources on ONGO Service Platform.