Editor’s Note

This article originally appeared in the Chinese media outlet 澎湃新闻. It describes the experiences of two Peking University students who took part in “Shared Future”, a project aimed at sending young Chinese volunteers to Turkey to help the many Syrian refugees on the run from the civil war that is ripping their country apart. This project is the first one of its kind run by Chinese organizations, and we hope that more will follow.

Since the “Arab Spring” begun in 2010, extremism and escalating civil wars in the Middle East have led to significant death and destruction. The violence has taken the lives of 180,000 Iraqis and 470,000 Syrians. Furthermore, 6.5 million Syrians have been displaced internally, and another 4.8 million have fled the country. Under the coordination of the United Nations, many entities have participated in humanitarian efforts for refugees, with NGOs and civic groups playing major roles.

This kind of work is rather unfamiliar territory to many Chinese people.

In Turkey, one of the primary destinations for these refugees, the government has established refugee camps to handle the influx of people. However, the majority of Syrian refugees have not taken shelter in these camps. Rather, most live amongst the general population. Fittingly, humanitarian efforts targeted at these refugees are broken down into two types: assistance for those at refugee camps, and assistance for those living in the community. The Turkish government and the UN Refugee Office are responsible for helping the refugee camp population. Out of concern for the protection of refugees, only UN bodies or NGOs working in cooperation with the UN are allowed into the camps. Other NGOs are not permitted at the camps. With regard to refugees living amongst the general populace, with the exception of public services and facilities provided by the government of Turkey, help primarily comes from NGOs.

“The strong development of Turkey’s NGO sector is a fairly recent phenomenon”, Nizip’s YUVA project manager Tara told us.

Many Muslim scholars believe what the Middle East needs are effective social and economic strategies and policies in order to address the complex, non-religious factors behind this violence and its harsh impact. They also believe cultural, racial, and religious factors should be considered, but that these are not the main reasons behind the problems of unemployment and marginalization.

This is also the “point of departure” for many NGOs.

According to a report by the Center for the Advancement of International Law, Chinese civil society is still in the “exploratory phase” when it comes to internationalization. Most overseas activity is led by civil society organizations with a government background, while international participation by independent groups remains fairly weak. This is due to a lack of four things: dedicated offices, specialized personnel, regular project work, and stable sources of funding. In many Chinese internet forums people have expressed the belief that the country should deal with its domestic problems first before addressing foreign problems, and disapprove of NGOs providing help overseas.

The “Shared Future” project is China’s first volunteer effort for refugees in Turkey organized through official channels. As such, it can be seen as a pioneering project.

Volunteers and refugees taking a photo together in the border regions between Turkey and Syria. In the center is Ken Yang, fourth from the right is Yuan Man. The person taking the picture is named Youssef

The humanitarian assistance and development project is sponsored and jointly led by the Refugee Law and Policy Research Group of the Center for the Advancement of International Law and the China Youth Foundation. The project is aimed at advancing the participation of Chinese youth in international exchanges and improving the lives of refugee children. It has become a real force in the realm of global humanitarian assistance and a visible sign of Chinese youth assuming a greater share of the burden of international responsibility. Currently, the project’s major activities are aimed at bringing young Chinese to Turkey, where they can provide education and other support to refugee children.

The Center for the Advancement of International Law was established in 2012 as an independent domestic NGO. It aims to promote and enhance Chinese participation and influence in the areas of international law and justice, giving China a greater voice than it previously enjoyed.

What exactly the Chinese can do is the question two volunteers, Ken Yang and Yuan Man, set out to find an answer to. One of them is a student of international law. The other is fluent in Arabic, has been to a refugee camp in Jordan, and is Muslim herself. Nevertheless, the trip was still full of surprises.

View from the volunteers’ commute. A lone pistachio tree is visible sprouting from the dry earth in early spring. Photographer: Ken Yang

Tara

Tara lives alone with her four cats. Photographer: Li Dan, journalist for The Paper news

After flying from Istanbul to the Syrian border, the volunteers were greeted not only by the bone-dry landscape, but also by Tara’s warm hospitality.

Tara is the only older person in YUVA and an American West Coast leftist, but she is very down to earth. She has always been committed to action, asking: “are you an armchair activist blowing hot air from a prestigious school, or do you choose to act?”

She originally planned to stay just one or two years in Turkey, and never imagined that 25 years later she would still be there. At the border town of Gaziantep, Americans are rare. Ken Yang said that some locals see NGOs as unwelcome foreign interventionists, or as “outside agitators”. When Tara was asked whether she is seen this way as an American doing NGO work in Turkey, she responded by saying that she is not an “agitator”, but rather, an activist.

Ten years ago, she went to Afghanistan to participate in training. She did not dare tell their parents, only notifying her father upon arrival at the airport. Her father wondered aloud how he would inform her mother. Her mother, however, reacted by saying “Tara went to do what she believes in.” Tara felt very lucky.

In Turkey, she first attended the University of Istanbul to educate and train other in the work of civil society. After leaving the university, she began running a female empowerment organization, believing strongly “that women should be able to safely go home alone.” She also sought to help those who have never been employed to earn their first paychecks. Later she met her Turkish partner, and together they founded YUVA, which means “home”. With some funds they began their work, choosing initially to focus only on environmental protection and civil rights.

In 2013, the worsening situation in Syria drove a large number of refugees to seek safety over the border. The Greek island of Lesbos sits near the western coast of Turkey. It is home to a very high concentration of refugees. In 2015, the number of refugees began to rise rapidly, and the crisis saw thousands of people crossing the border every day. Many attempted to make the perilous voyage on rickety boats, leading to many deaths. One day, a Syrian man came to Lesbos to identify and claim five bodies. This was heartbreaking for Tara.

Unable to stop them from boarding, she wanted to give them fewer reasons to board the boats and more reasons to stay in Turkey. YUVA began to provide community-based informal school curricula for refugees. “There is no single solution, we just want them to live happier and more dignified lives.” They organize all sorts of activities to promote the integration of Arabs and Turks, such as song, dance, and football. Both Syrians and Turks are invited to these events.

Tara is well aware of the difficulty of being a “pioneer,” which is why she warmly received the first batch of volunteers from China. “The strong development of Turkey’s NGO sector is a very recent trend, and now there are more international projects that are very encouraging, including your arrival.” She reminds us that as a volunteer, you must speak the local language and have a certain understanding of the existing local systems.

YUVA

Turkey’s NGO sector is diverse, and research last year by the Director of the Center for the Advancement of International Law helped paint a full picture of how the various refugee-focused NGOs work. The larger local NGO in Gaziantep is called ASAM (Association for Solidarity with Asylum-Seekers and Migrants). As an executive partner of the UNHCR’s Office in Turkey, it carries out some of UNHCR’s duties. It also provides refugees and asylum seekers with psychological counselling and legal advice to help them access education, healthcare and other basic rights and services.

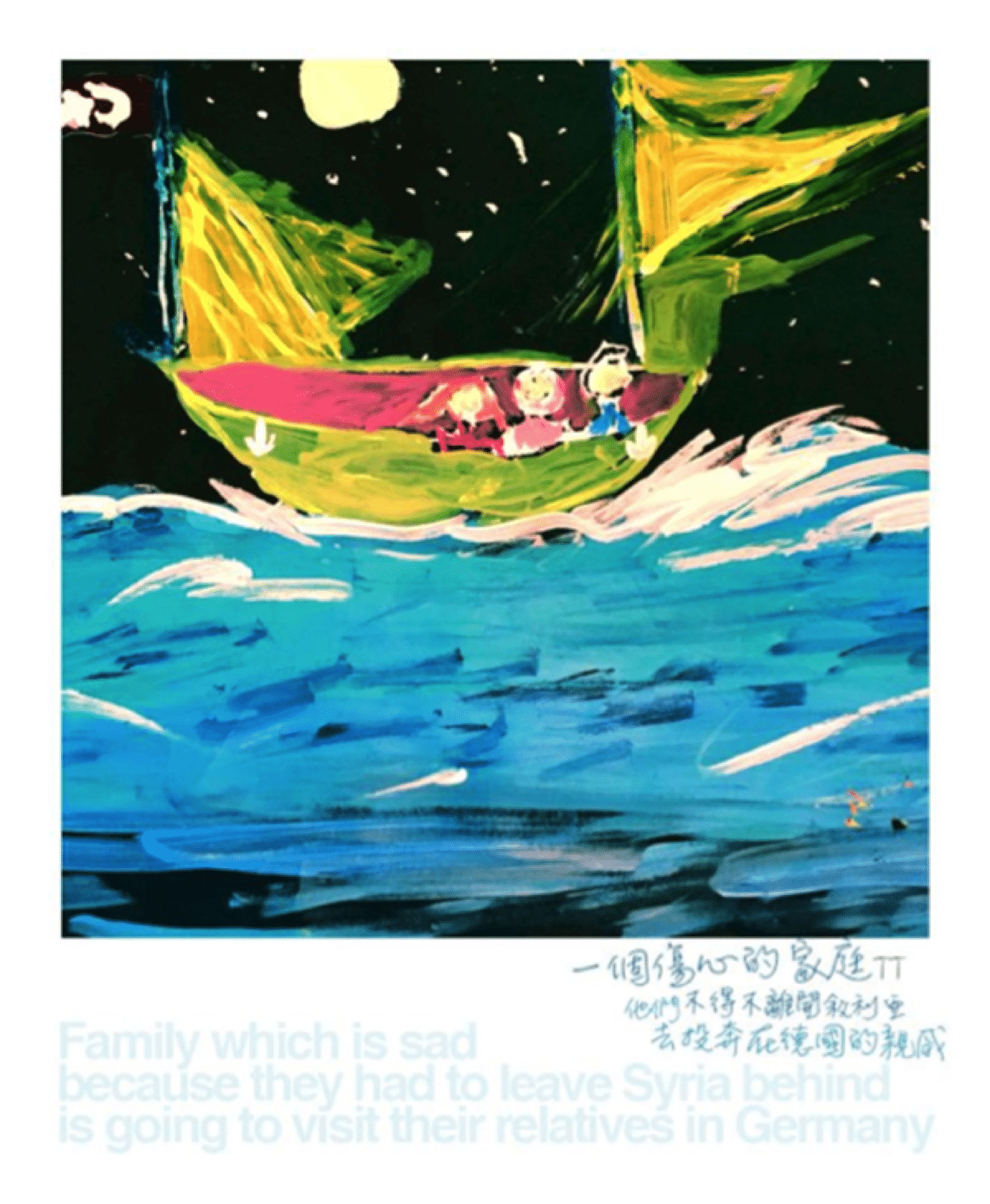

In order to integrate refugees into the local area, and to help them cope with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), they invited Turkish painting masters to teach children to paint. Each time, five Syrian children and five Turkish children were brought together to learn and paint together. ASAM cooperates with the Center for the Advancement of International Law, and last year the organizations displayed and auctioned off 50 of the center’s paintings in China.

Art exhibition card

The current dilemma is that Turkish schools are unable to provide adequate educational resources for refugee children, and some refugee families are unable to financially support their children’s formal education. Some refugee children even take up jobs to help support their families. Many NGOs have become aware of the urgent need for informal education, such as that provided by YUVA.

Tara said: “We cannot change their lives, we can only make them happier and stronger, so that they can change their own lives.” This has become a real community and a home, and many people spend a lot of time here. On the first day the volunteers arrived, they were warmly welcomed by both the staff and the refugees. One man came to speak, but after just a few words it was apparent he came to ask for money, putting the staff in an awkward and embarrassing situation. One of them said that they “do not want refugees to develop a mentality of dependence on handouts. “

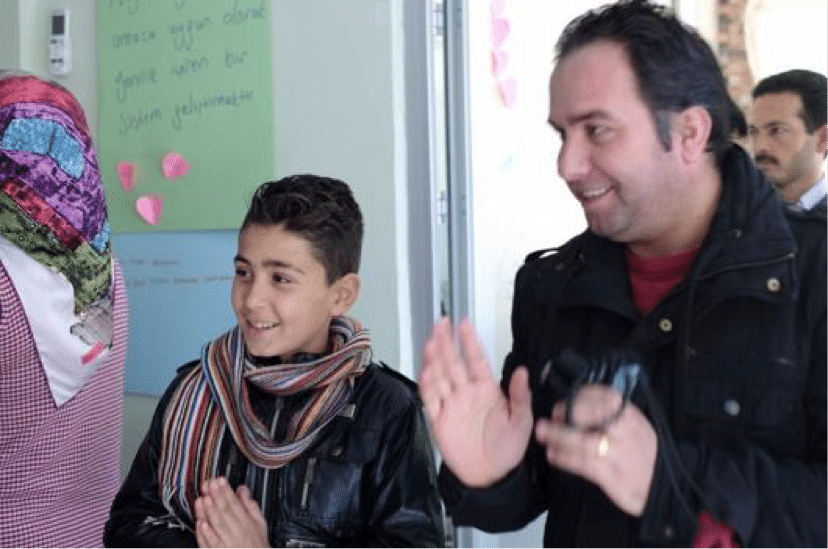

On the first day, the director of the vocational center and a refugee boy came to welcome the Chinese volunteers. Source: Li Dan, news correspondent for the Paper

YUVA has two centers in Nizip: a Community Center and a Skills Training Center. The former, through the efforts of social workers, seeks primarily to protect the refugees and provide psychological support. The latter aims to equip refugees with the practical skills necessary to find a job.

Community centers mainly support minors and offer language courses, in order to promote the equality of refugees and locals and help children overcome pain and fear. Social workers would like to do more outreach in the community, but during the past two years the government has introduced various restrictions on home visits. This means they have to wait passively for the refugees themselves to come and seek help from YUVA. Recently, YUVA’s visits to schools have been suspended while they wait for approval from the Ministry of Education. Social workers are also going to carry out activities in the Turkish community to prevent Turks from developing prejudiced beliefs that refugees are draining local resources.

A volunteer teaches a refugee child to play with a Rubik’s cube. Source: Ken Yang

Ken Yang meets the head of the community center, Ayhem, in his office. Source: Li Dan, news correspondent for The Paper

Ayhem, the head of the community center, is a Syrian who came to Turkey to study science. Later he began working for the NGO, dedicating himself to resolving the health problems faced by refugees.

He told us that many of the tens of thousands of refugees in Nizip were unable to seek medical treatment, and only those who had been registered as refugees and who had received an official ID had access to the public health care system. But since the number of refugees there is much higher than in other regions, Gaziantep became the only area where the registration system was closed. This has led to an urgent need for medical supplies for the local area.

Osman is the head of several neighborhood skills training centers, and has been working at YUVA for four years. His work is grounded in practical realities, as he believes the training centers to be more practical and useful than the social work centers, as they help people find ways to make a living. “They teach Arabic there, but no one uses the Arabic language in Turkey.” Only 30% of the refugee children are receiving systematic education in school. “Education is important, but Syrian families are so large that if they all receive an education, there is no way to make a livelihood. We struggle hard to find the right balance, and our center is thus trying to jointly address both livelihood and education.

The arrival of Chinese volunteers was both refreshing and surprising to the two staff members at the center.

Ken Yang and Yuan Man

From the “Arab Spring” to the “Arab Winter” Ken Yang, who studies International Law at Peking University, has constantly been interested in developments in the Middle East. “When the Arab Spring begun, I had not yet graduated from high school. As we entered the ‘Arab Winter’, I had just begun taking an interest in international law, and thus started to think about it from the angle of international law. I also began wondering whether I had the responsibility as an individual to help refugees, and whether I had a moral obligation to separate the issues from those of sovereignty and borders. At the very least, I didn’t think it was just a question to be pondered upon by the intelligentsia.”

He found himself disappointed by some of the arguments espoused by Chinese internet-users: “To some people, all of the unrest and suffering in Syria is caused by “troublemakers”, who have only themselves to blame. The silent majority who does nothing to stop these troublemakers also have no one but themselves to blame.” As he read more and more material on the issue, he felt that things were not so simple. Moreover, “no matter who caused this suffering, it is suffering nonetheless and should be reduced.”

In February last year, Liu Yiqiang went to Turkey to study the NGOs helping refugees. He was moved upon seeing the paintings created by the refugee children, and arranged for them to send 50 paintings to China for auction. He needed a student to help curate and select the art works for exhibition. Ken Yang then joined the team, helping to design and plan for the exhibition.

In the second half of last year, Ken Yang went to the Columbia University School of Law as an exchange student. There he saw students who had the means to take direct action in third world countries under the leadership of their professors. He was surprised by this and eager for similar opportunities. “Back home, there is often no opportunity to take action, even if one wanted to.” When he saw there was an opportunity, he decided he would not pass it up.

Last December, with the first batch of funds finally in place and the conditions ripe for volunteer work in Turkey, Liu Yiqiang asked: “Do you want to try?” This January, before returning from the United States, Ken Yang wrote a long letter to his parents explaining the cause, significance and possible risks of the project. Upon landing back in Beijing he met his parents, and immediately they said he could go.

The scope of Yang’s research also includes the discourse on human rights in the post-Arab Spring era, which has gradually faded as the political situation there has evolved. He wanted to examine the limits of human rights and whether to shape human rights into an all-encompassing, utopian thing. “Previously, I was overly hopeful, only to find that there were times when we could not help. It was then that our opponents found it easy to discredit our efforts. I agree with the “minimalist approach” advocated by Michael Ignatieff, in which human rights should be discussed and addressed only in extreme circumstances, such as during times when civilians are being killed en masse. When the war in Syria is framed as the result of a lack of human rights, it is good for neither the cause of human rights nor the people themselves.”

Before his trip, Ken Yang questioned whether refugees really did not want to return home. When some people in internet forums back home stigmatize the refugees as simply migrants seeking better economic opportunities, he argues that “illegal immigrants and the people escaping Aleppo are obviously not one and the same.”

“Syria is a highly educated country. On Liu Yiqiang’s last visit, he encountered many Syrian people who spoke English. Those who don’t see the refugees’ circumstances with their own eyes do not understand.”

Because of a lack of Chinese presence there, as part of the first batch of volunteers, he shouldered much of the information-gathering burden. He brought three cameras and several rolls of film, hoping to bring back some images. “Not exactly images of suffering, but rather images reflecting ordinary people.”

The other Chinese volunteer is also from Peking University.

Man Yuan teaches Chinese calligraphy to refugees Source: Ken Yang

She is Muslim and had wanted to major in the Arabic language ever since high school. In high school she read a line in the preface of Ma Jian’s Arabic translation of the Analects. It read “I am Muslim, as well as Chinese. As such, I shoulder responsibilities both religious and national. I am determined to fulfil both obligations.” Upon reading these words, she immediately felt a call to action. As the second-ranked student in her high school, she was accepted to Peking University’s Department of Arabic Language. Yuan Man is now in the second year of her graduate studies, and happens to be minoring in the Turkish language. The project was too close of a fit for her to pass up. In her eyes, Arab nations are not strange or unfamiliar. In fact, she had previously traveled to the region on multiple occasions and communicates regularly with several friends there via WeChat and WhatsApp.

Last summer, she came with a team to Jordan to visit a camp for un-registered refugees. “There was a Syrian businessman living in poor conditions who pulled out a notebook full of poems he wrote describing his love for his people and his motherland. At the camp, I recited a poem taught to me by an Arab student at Peking University, and immediately my eyes swelled with tears.”

Due to the spate of recent terrorist attacks in Turkey, her parents were worried about her taking this trip. But in the end they said: “You should do what you feel is right.” She told the reporter that with their blessing, “I did not hesitate for a moment. When my Arab friends need me, if I can offer even a little help or play even a minor role, then I will be very happy.”

When they came to Gaziantep, they discovered a situation very different from what they had imagined. “Originally, we intended to focus on the refugees in most dire need of help, but it turned out that this was not possible,” he said. “After all, Chinese NGOs cannot donate money directly.”

“Classic Western films always have a fly-by-night stranger from out of-town who comes to punish evil and reward the righteous. However, we discovered we could not be that kind of hero with a dramatic solution to whatever problem. Instead, here we just have to persevere,” said Ken Yang.

The traumatic story of the refugees is too jarring for those who haven’t experienced war. Because the ratio of English-speaking refugees to French-speaking ones turned out to be lower than they had imagined, the majority of Yuan Man’s conversations were conducted in Arabic. These conversations in Arabic also had the greatest personal and psychological impact on her.

“To tell the truth, on this trip I often find myself feeling a bit powerless. Perhaps due to my personality or language abilities, they have treated me like an intimate friend. As I listen to their stories, my brain paints a picture that leaves me both shocked and saddened. I know my attempts to comfort them are never going to be enough. We can never truly feel the same feelings they have.”

Her deepest feeling is of being unable to feel what they feel. Despite their bleak and destitute conditions, these people try to maintain a positive attitude, and not allow the circumstances to diminish their friendly and generous nature.

In fact, the presence of Chinese volunteers has brought a lot of joy to the people. They are full of curiosity and questions about Chinese people and society. They take turns inviting the Chinese volunteers to their homes as guests, and talk with them all night long. Every morning, they use what Chinese they’ve learned to wish the volunteers a good morning in their native tongue.

During this period, Ken Yang has made Chinese food for the refugees. He also lent his camera to refugee children eager to study photography, and taught them how to take pictures. He even developed the film for them in a studio and gave them printed copies. Yuan Man introduced some refugees to Chinese calligraphy, and the community leader has requested more courses combining Chinese and Arab art in the future. “If volunteers came to teach such a course, the people here would be very interested.”

The visit by the first batch of volunteers has been too short, and what they most needed was to gather information over a limited amount of time in order to develop a plan for longer-term volunteer programs.

After they went home a Turkish teacher, who did not speak any English, used the WeChat translation software to translate his message from Turkish into English: “All friends missing you.” “Again you come?” Both volunteers are looking forward to applying again this summer. When they visit, they may bring along more volunteers and stay for a longer period of time.

“Shared Future” project manager Zhou Tianyi told reporters that in subsequent volunteer trips there will be a higher proportion of volunteers who speak Arabic. They will also design curriculums that include music, art and sports courses in order to help both adults and children release and express their feelings. “By promoting communication and exchange, fresh and beautiful memories can help dilute memories of their past misfortune, thereby reducing these negative memories’ impact on their future.”

“Shared Future” also plans to promote mutual understanding and communication between Chinese and Arab culture, so that young people can understand the unique things in each other’s culture, rather then jealously guard their own.

Liu Yiqiang said they hope to establish a broader range of mechanisms to reach more students in order to select the very best candidates.

To conclude, Ken Yang shared his thoughts with the reporter: “America’s first black Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall used this sentence to sum up his career: he did what he could with what he had. Perhaps in these volunteering efforts, we should divorce from the tendency to overthink how to help, and instead focus on getting started right away. In the ‘long term’, the refugee children may need more systematic formal education, but this kind of help is one which we cannot provide directly. It also may not be what is most needed at this time. They need someone now to help them express what they feel after the trauma they endured. By focusing love and attention on these children, perhaps the volunteers can alleviate their feelings of anger and disillusionment. These small things that may not be given due attention to in the Chinese context may be precisely what they most need at the moment, and what we can do best as outsiders.”