On the Kaerxi Tibetan community in the Maqu grasslands, within the first bend of the upper Yellow River, brand new solar panel units gleamed in the sun among the yaks roaming the fields. Later in the night of the Tibetan plateau, these units will bring light to the nomadic tents of the natives and power their electrical appliances, providing them with unprecedented electricity access. However, these solar panels bring to the primitive grasslands more than elevated life standards and convenience—they are, in fact, part of Green Camel Bell’s greater campaign on empowering native grassland nomadic populations to take part in the campaign for the SDGs (sustainable development goals).

The grassland dilemma

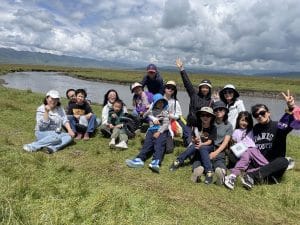

The Kaerxi Community, based in Awangcang, Maqu County, Gansu Province in western China, is a traditional Tibetan nomadic community. Living amidst the cold and windswept grasslands, the Kaerxi people maintain a nomadic lifestyle, moving with portable homes and relying on animal husbandry for their livelihood. As the indigenous people of this region, they have preserved a traditional way of life that is a vital cultural heritage.

Maqu grassland

However, both the indigenous way of living and local environment is being challenged. Kaerxi face the classic grassland dilemma: as the community population increase, the people must rear more animals to sustain average income, but the increase in livestock can deplete the limited grassland resources and ultimately lead to irreversibly reduced production, resulting in a vicious cycle. Furthermore, grassland nomads cannot stay at permanent regions due to their nomadic nature, as the grassland takes time to recover. While the natives stay in permanent settlements for winters, the lack of permanent residence during summer still makes secondary industry such as yak produce processing difficult because electricity can be hard to come by.

The people of Kaerxi were, just like many other indigenous populations in tough climates, facing a difficult situation. If the hardships persist, these people may have to leave their own life entirely and migrate to seek for a living. Their current style of living, which features burning biomass fuels such as yak dung and potential overgrazing, brings environmental damage to the fragile grassland area. The reliance on biomass fuel is especially problematic: it is not an efficient fuel, pollutes the air when it’s burned, doesn’t last long, and cost a lot of labor to collect, dry, store and move. However, it’s hardly sensible to ask them to reduce living standards for the sake of environment when sustaining life on the grasslands is already a challenge.

Burnning yak dump

Our solution: solar energy and eco-tourism

To improve life at Kaerxi, it is vital to look from another angle. Combustion fuel works poorly in high altitudes, the nomad’s moving life won’t allow for geological energy, but high altitudes also means good conditions for solar energy. Maqu County has over 1400 hours of effective photovoltaic power generation throughout the year. Besides, if the solar units can be combined with storage capacities, these off-grid photovoltaic energy storage systems can not only improve living conditions but also help locals join the effort for sustainable development.

The units are developed for efficient use in migratory life contexts. The technical team has planned out the installation process in great detail in advance, taking into account the optimal power generation angle and the necessity for the installation area to be separated from humans and animals to ensure safety. The cement foundations of typical units, which makes moving them difficult, are replaced with a long ground anchor that can be dug up or replanted easily. In strong winds, the herders can use ropes to ensure wind resistance. The lithium iron phosphate batteries that come with these units can operate well in low temperatures down to -20℃, and can easily store enough energy for life appliances such as light bulbs and water pumps, so no additional storage is necessary.

GCB volunteers trained by professional technicians introduced these units to the locals. Herders and community technicians are trained with necessary electricity operation theory as well as how to operate and maintain the units safely. The herders also participated in the whole installation process so they can learn all about the mechanisms of different parts. After training, the herders can disassemble, assemble, use and maintain the system autonomously.

These units have great advantages in the nomadic grassland life setting. By providing stable electricity, they can elevate living standards as well as facilitate some secondary industries related to livestock rearing such as yak diary and jerky production. These new sources of economic income can reduce the pressure on livestock husbandry and consequently reduce pressure on the grasslands. New sources of income means less need to overgraze. The economic support also enables the indigenous people to maintain their own lifestyle and culture. Solar panel units brought all these to Kaerxi—a happier life, the ability to maintain the traditional way of living, and greener living. Now there’s no need to choose between stable electricity and nomadic life, no need to choose between greenhouse gas and overgrazing. It’s possible to have all if we find the right plan.

What next?

The panels are just the start. Now, the improved living conditions in Kaerxi means the indigenous people can have both their traditional lifestyle and the comforts of modern life, with no need to sacrifice one for the other. Solar energy makes turning the community into a net-zero emission community. The petrol fuels that once powered water pumps are now replaced by green electricity, and soon other changes can also follow: electric stoves can replace biomass fuel stoves; better electricity coverage can reduce the ever-increasing reliance on coal; ample electricity may be able to power electric cars, which are more effective in high altitude areas where fuel combustion is inefficient. The same solution can be easily to extended to communities around Kaerxi, and one day electric cars may run on the high lands of Tibet.

Beyond Kaerxi, the journey for empowering ethnic minorities to live sustainable (and happy!) lifestyles continues. On 2024/11/18, GCB will be holding a COP side convention where native folks, academics and social activists can share their experiences on indigenous empowerment. There are plans to collaborate with local governments and community to establish long-term technical support mechanisms to ensure the continuous maintenance and upgrades of the equipment. System upgrades and further community education are on the schedule and on the way, and as the project gain social exposure, more and more volunteers are coming in to join the effort.

Through the volunteers, GCB seek to bridge international experience and knowledge with the needs of communities. We learned a lot from prior successes, and we hope the success at Kaerxi can provide experience for green power generation in similar highland communities such as the Mongolian highlands.

As the chill of night fall on the Tibetan highlands, tents scattered across the dim plateau lit up like stars. It is up to all of us involved to keep these sparks going and spreading, and perhaps one day many such stars will shine around the world.

Bio:

Li Wanlin is an assistant researcher of the Lanzhou-based NGO,Green Camel Bell.