Editor’s Note

This is CDB’s translation of the talk that Prof. Tao Chuanjin (陶传进), from the School of Social Development and Public Policy of Beijing Normal University, gave at the 11th Annual Symposium of the China Foundation Forum, held on the 22nd and 23rd of November 2019 in Fuzhou, Fujian Province. The talk analyses some of the underlying trends that lie behind the current state of charitable foundations in China. You can find the Chinese original here.

Let’s use five graphs to depict the overall development of the sector (of charitable foundations), looking beyond just the events of the last year. But whilst it may be possible to trace changes that have occurred over the years, we must continue to focus on the most recent events to gain a complete understanding.

We want to use these five graphs to express our optimism about the development of the sector. What they display make this optimism easy, as we can immediately see why this sector is developing in the way that we hoped it might. Yet the more we progress, the more challenges we encounter, making it easy to lose sight of the optimism behind the challenges. Only as we continue to work to overcome these challenges can we fully unleash the optimism that is hidden within them.

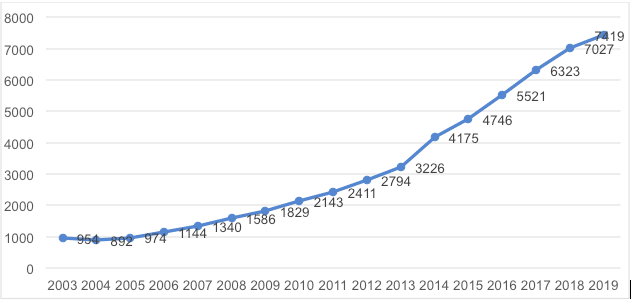

Graph #1: The increase in the number of charitable foundations

Picture 1: the number of charitable foundations recorded in China over the years (Data Souce: China Social Organization Public Service Platform, accessed October 2019).

The first graph shows the change in the number of charitable foundations up to the 31st of October 2019. We now have over 7000 foundations operating in China.

Within the charity sector, we all remain hopeful that the curve will continue in this direction and growth will continue to pick up speed. The quicker the growth, the greater the slope of the curve.

But we should be wary of the growth curve becoming too steep, for this may wear down those who are leading the sector. If we grow tired, we should lower our expectations and not create excessive pressure for ourselves, allowing us important space for everyone to rest and recuperate.

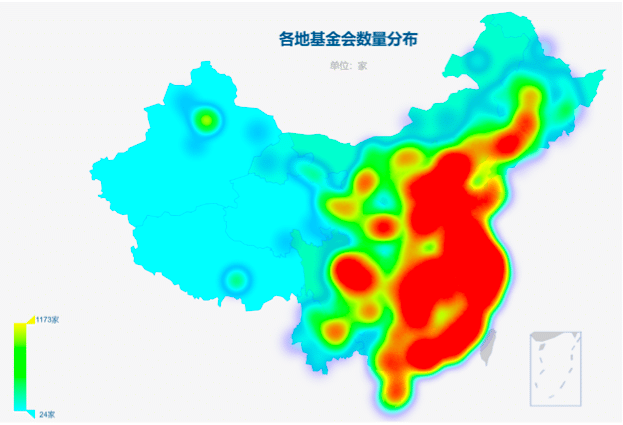

Graph #2: The geographic distribution of charitable foundations

Picture 2: Heat map of foundations around China (Data Souce: Foundation Centre Network)

This is a heat map showing the distribution of foundations across the country. You can clearly see that there is a positive correlation between the number of foundations and the level of economic development. That is to say, the more an area sits at the frontier of economic, political and cultural development, the more we can see the emergence of a large number of foundations there. This gives us an optimistic picture, for the foundations have gradually emerged alongside social progress, ultimately raising the charitable force of society to a higher level.

However, according to some studies, although the number of social organisations (including charitable foundations) is positively related to the level of regional economic development, their capabilities may not be increasing in tandem with demand. As such, we must continue not only to increase the number of foundations, but also to strengthen their capability.

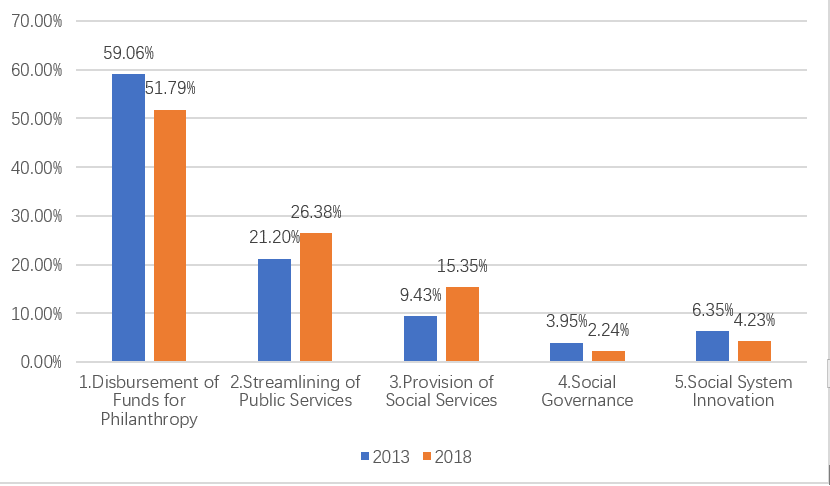

Graph #3: Changes in the types of charity projects

Figure 3: The proportions of the different levels of charity projects run by Beijing foundations (source: collation of data from the annual inspection of Beijing’s foundations)

The graph above depicts the current state of affairs for Beijing foundations; it is not nationwide data. It comes from information gathered through our annual inspection work on foundations operating in the Beijing Municipality. The graph shows an analysis of the different projects levels, taking the 1511 charitable projects (1495 of which have effective data) carried out by 270 foundations in Beijing in 2013, and the 3129 charitable projects (3120 of which have effective data) implemented by 631 foundations in Beijing in 2018.

What is meant by the “level” of a project? Charity projects can be divided into five levels according to their technical content, ordered from left to right in the figure above. The five levels are the disbursement of funds for philanthropy, the streamlining of public services, the provision of social services, social governance, and social system innovation.

This subdivision into five levels bears several implications. First of all the technical content gets more complex from the lowest to the highest level, and the challenges the foundations have to face are increasingly difficult. Secondly, the depth of the general public’s participation in social governance also increases from the lowest to the highest level. At the higher level it is no longer about a simple investment in funds or time, but also about embodying the values of kindness and respect, and taking part in these activities.

Government purchases of services provided by social forces tend to occur particularly around the third or fourth level. This implies that, in the process of promoting the transformation of social management, the government transfers its own core functions to social organizations and provides assistance in the delivery of funds. However, one difficult aspect of this is that social organizations show a lack of competence in this respect, and yet the foundations’ own fundraising channels are inadequate and their participation is not high. Furthermore, the work of foundations tends to be confined to their own field of operation and the great majority of projects are still circumscribed to the first and second categories.

Moving on, we can observe in the graph that the height of the columns steeply decreases from left to right. This indicates that the majority of problems are still addressed through the disbursement of money, and that our technical level and thoroughness in solving social problems are still quite insufficient. This is an arduous challenge that we are currently faced with.

Nevertheless, there are some aspects of the graph that allow us to be optimistic. As we can see for every level there are two different columns, a blue one and an orange one, representing data from 2013 and 2018 respectively. After five years of development, we can notice that the proportion taken up by projects in the first level shows an evident drop, whereas the second and third levels show a clear rise. This demonstrates a direction of development inherent to social organizations: they are making attempts to standardize their work and provide more compassionate services to society.

Unfortunately, the proportions taken up by the fourth and fifth levels appear to be very low, demonstrating the high-end skills requested for the management of social affairs. As long as it is impossible for us to fulfil such requirements, these functions will keep falling into the governmental domain and it will not be possible to transfer them to society. Despite the noteworthy efforts aimed at handing over certain functions of social management to social organizations, such as the creation of organizations at the community level, the implementation of consultative systems and the development of community building activities, due to capability issues it is still not possible to carry out substantial aspects on a larger scale.

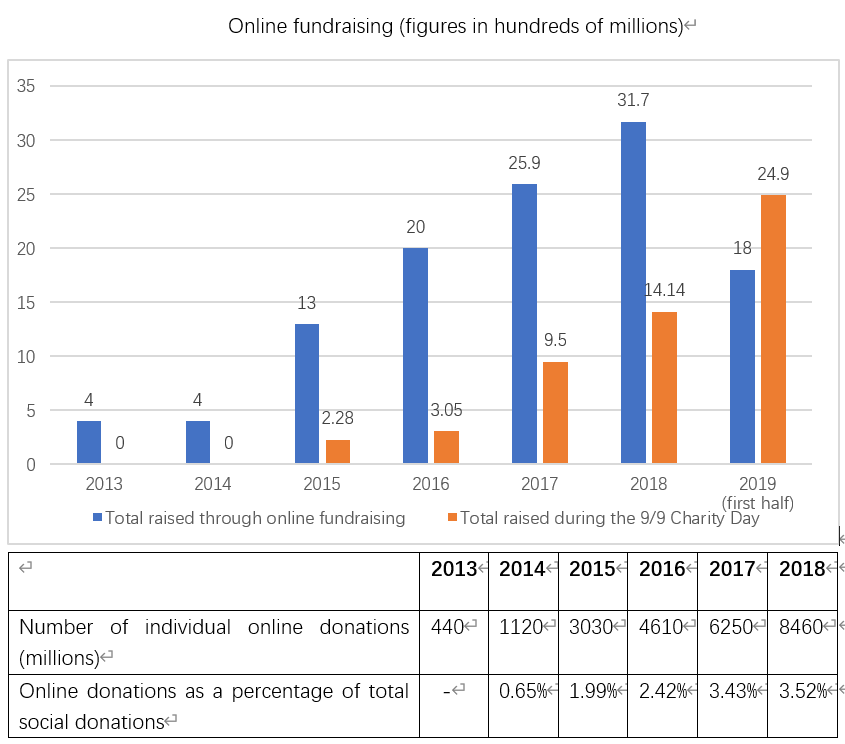

Graph #4: The changes that online fundraising has brought to foundations

This is a graph on the growth of China’s online fundraising in recent years. The data is divided into two categories, one for the total amount raised through online fundraising, and the other for the amounts raised during the annual 9/9 Charity Day. What needs to be noted is that the data for 2019 only covers the fist half of the year until June 30th. Due to this, the figure for this year is only showing around half of the normal level, but after the 9.9 Charity Day the figure would almost reach the total.

The graph shows three notable values: the total amount of online fundraising, its proportion within the total charitable fundraising, and the number of people involved. These three figures have been increasing rapidly year by year, giving us another reason for optimism.

An explanation needs to be added regarding the proportion of online fundraising. The figure is not high, it is in the single digits. However the money raised goes purely towards the operations of charity organizations and programs, so it has the same effect as a grant-making social welfare foundation. Most of the foundations in China are not grant-making, so the actual effect of this proportion of fundraising has to be multiplied many times.

But then another challenge emerges due to the large amount of irregularities appearing in this emerging sector, such as the widely condemned “fundraising tricks”. When we track down this phenomenon we find a lot of dissatisfactions and complaints. It seems like this sense of social injustice has reached a level where, every time fundraising efforts reach a peak, they are always accompanied by a lot of indignant voices. This leaves a bad impression and may even cause people to doubt the purity of intentions of the charity sector.

Especially during the 9.9 Charity Day, a large amount of funds is raised in a short period of time. At the same time, many social welfare organizations are in the process of “splitting their share”, and in many places the phenomenon of “grabbing money” has been bluntly displayed, severely testing the regulations and people’s hearts.

However, even here there exists a lot of positive potential. This is the first time in history that a system of regulations of such scale is set and ran by the society. It is a rule-fulfilling system set in a spirit of following contracts. Although this form of relationship with the rules did not receive enough respect when it was first instilled in the society, it has kept on expressing its power. The following aspects deserve particular attention:

Firstly, the rules on fundraising are constantly in a process of transformation. In fact, it is reasonable that more changes should take place, because these changes reflect the previous problems. Secondly, the original intention behind the regulations: in this case Tencent Charity reveals a strong positive intention to make things right. They recruited experts and scholars in the field to discuss, establish, and amend the regulations, increasing their reasonability in a sustainable way. Thirdly, the irregularities within the field come from organizations that do not abide by the rules. However, it is us, the non-compliers, who at the same time complain about these rules. As long as we raise our own level of awareness, we can improve the situation.

Fourthly, it is particularly important that some of the pivotal charity organizations in the field (we temporarily call those organizations with long-term brand accumulation, large amounts of funds, and long-term interests “hub charity organizations”) are getting out of their passive situation, they are pursuing their own long-term brand construction, pursuing the credit mechanism and an awareness of the rules. They are another force that allows the rules in this social field to be actively implemented, and they stand side by side with Tencent Charity. From this perspective, these seemingly negative and pessimistic phenomena are actually giving birth to a very positive and optimistic potential.

Graph #5: The tic-tac-toe structure of social organizations

| Small, grassroots

Social Organizations |

||

| Advocacy

Social Organizations |

Governance

Social Organizations |

Official

Social Organizations |

| Other

Social Organizations |

Figure 5: the “tic-tac-toe” structure of social organizations

This is a tic-tac-toe chart, from which we can best understand how we should treat the development of social organizations, for instance whether we should have an optimistic or a pessimistic view.

In this picture we first create a middle area, where we find the governance organizations. This means that first of all, the organization follows the principle of democratic governance internally; and secondly, the organization has entered the system of social government functions externally. This is about giving public services, not about politics.

Social governance refers to the participation of the organizations themselves in the public service system. The concept of categorizing organizations into four types was proposed in a government document several years ago—the categories are charity and philanthropy, business associations, social services for urban and rural communities, and science and technology organizations. This division into four kinds caused people to ask themselves: why put them all together? After careful consideration, however, what transpires is that the common denominator is social governance. That is to say, these types of social organizations all are contributing to the provision of public services, whether that be in the form of basic charity or participation in high-level social governance.

Once this middle ground has been established, the next point is easy to understand: surrounding it on four sides are diffierent kinds of “social organizations, whether that be according to the traditional classification methods of sociology or traditional society, seeing and understanding them as social organizations becomes natural and expected. However, at the moment, the social organizations engaged in governance have withdrawn behind the scenes. These are not the social organizations that we emphasized earlier who register with the civil affairs department, and most of them even have some risky characteristics. This is the opposite of policy reform.

There are some important characteristics in particular that need to be presented here. Social governance-oriented organizations are a new addition to modern society, appearing only in recent decades. The first important characteristic is that they have been established according to present day social organization governance systems, and are quite different from the traditional kinds of social organizations. These organizations are registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs as legally operating entities, and have entered the field of social governance to provide public services, acting precisely within the range of functions of the government in the past. Because of this, the current shift of government functions has been dependent on the emergence and competences of these types of organizations. Therefore, there is a clear difference between this type of organization in the middle of our graph and the four surrounding types.

After making out this grid-shaped structure, we can then present an image of the current top-down push for social governance reform, and why this is both a cause for optimism and a challenge.

First of all, in the middle zone of the grid, the national push for policy reform of governance organizations has already reached its full horsepower, even in the eyes of many local government officials who are wary that excessive enthusiasm could damage the long-term viability of these organizations, as the side effects (various types of risks) from reform have already created significant pressure on social stability. We can even ask a comparative question: in the field of social welfare, can support for these types of spontaneous, self-started social organizations actually reach this level? In fact, policy support from the government, whether financial support or support through lowering the threshold for entry, has all reached this level: even the most extreme efforts of social organizations have a very difficult time achieving it.

Secondly, at the level of the management of grassroots social organizations and of the management of government procurement of services, government management and the management of implementation systems, it is possible that there are two additional components at work. The first component is a top layer of administrative intervention, which is to say, matters that fall within what is considered to be the scope of social organizations’ autonomy also have an added layer of control and intervention. The second component is a layer of political elements, particularly the doubts as to whether these organizations are truly governance organizations.

Returning to the image of the grid pattern, we first need to distinguish the intermediate zone of social governance organizations. Here we need to provide an environment in which social organizations can operate autonomously in accordance with the law, without superimposing administration and politics. In short, this is equivalent to confusing the organizations lining the outer levels of this grid with the organizations in the middle zone that are being pushed forward by top-down national reform efforts, heaping the mistrust of the outer organizations onto these middle organizations. This is a big challenge.

Using this grid illustration also shows that even with the strictest classification methods, the middle zone can at least be treated separately. Seeing such social governance organizations operating in accordance with the law, it is necessary to give them support. They are the backbone of our country’s social governance reform.

Of course, officials in the management system can say that they don’t have the capability to identify the middle zone, and it can even be said that without strict oversight, the middle zone cannot be distinguished. It is precisely such an irresponsible attitude that has caused the failure in the development of social organizations to achieve the effect that the central government’s vigorous promotion of social governance reform should accomplish.

The ability to distinguish is one of the core manifestations of management ability. After distinguishing, separate treatment is an effective guarantee to ensure the advancement of social governance and the minimization of risks. If this is not done, management has failed to accomplish their job requirements. Of course, based on managements’ functional and institutional positioning, we cannot ask too much from them, but it is for this reason that we have hired third-party agencies in the evaluation of government purchases of services and the evaluation of social organizations, and it is assumed that the third-party has the ability to be professional and take responsibility independently. The issues is that it if the will and work methods of administrative officials are brought to bear on the third parties, this is regrettable and should not occur.

Thirdly, we must acknowledge that the institutional arrangements for reform have been done to the best degree. For example, the government has not only funded the purchase of public services of social organizations, but also transferred its own functions and delegated the power of evaluation to non-governmental third parties.

However, it is this so-called “third party” that caused a problem, and this third party is all of us here and our friends. When we evaluate as a third party, our approach actually means we take on the role of a “second government.” On the one hand, we try to figure out or explicitly accept Party A’s will; on the other hand, we lose our professional ability in the evaluation process, and the professional ability of the appraiser might be far worse than that of the appraised; moreover, we pay too much attention to the action itself, expand the scope of what is considered to be the norms, and occupy the space within the autonomous operation of social organizations. The feeling is similar to a teacher giving scores to elementary students.

This approach reminds one of the sort of regulatory model that you find in public institutions, and its effect is equivalent to governing over social organizations and making them lose their vitality. As a result, the third party embodies neither professionalism nor the advantages of assuming independent responsibility. However, precisely because of our social organizations themselves, the whole reform still carries a sense of optimism. Once we have improved our ability (and integrity) as the third party to a level where we can perform the job well, we can break through this ceiling and move further up.

From this, we can outline a situation in which social organizations have developed to a cutting-edge state: firstly, our entire field of social charity started from basic disaster relief and from the concept of civil society; secondly, we have gradually entered a field of deeper social governance, where we gradually acquired professional capabilities. Afterwards, the development of social organizations and the advancement of the transformation and reform of government functions both benefitted the society.

However, there is little interaction between these two phenomena. They both walk on their own paths, because government purchases of services do not absorb the “homegrown” forces of the field of social organizations. Once again, all of our social forces need to echo the trend of government-driven reforms. The transfer of government functions must be undertaken by social organizations, and the government’s funds to purchase services must be made use of by social organizations. This way, the reform will have taken another step forward. But at this time, the efficiency and regulation of the use of public funds has become a problem, and third-party evaluation agencies have become the most critical decision-makers of future development.

But this is where problems arise, and social reform seems to have hit the ceiling. However, we can certainly encourage third-party assessment agencies and other professional parties to have higher professional capabilities, a higher sense of responsibility, and not forget their best intentions. At this point we can break through this bottleneck and move forward.

The signs of development include the growth of social organizations’ capabilities, the transfer of government functions, and the transfer of governmental funds. The three echo each other. The assessment of third parties and the supervision of the government paint different landscapes. The advantages of social organizations can still be brought into play here, so the transformation of social governance can be continuously advanced and expanded and we can hold optimistic expectations for the path for social development.