Li Jiete is the founder of Banying, an organization based in Beijing dedicated to empowering Chinese women through creative work. CDB recently spoke to Li about her work, women’s rights, and how art therapy can help people who’ve experienced trauma.

This year Li’s organization will host the (2022) Women Arts Festival in Kunming, Yunnan Province. Every year, the festival is held in a different city, as women from different parts of the country often have different challenges. Yunnan was chosen thanks to its rich cultural history and diverse local cultural traditions. This year’s event will feature an exhibition, a theater therapy workshop, a poetry night, a performance art piece, and several roundtable discussions. Most of the artists invited will be from the local area, with 10 percent from an ethnic minority background.

What is your background and how did you become interested in art?

I initially studied art history at Smith College, a women’s college in Northampton, Massachusetts. After doing a master’s in New York I got a job working at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. Working there was a great opportunity in many ways, but I hit the glass ceiling pretty quickly. As a young Asian woman and a foreigner, it was hard for me to get promoted to any leadership positions, especially in a museum which focuses mainly on Western art history. After that I took a job at the National Portrait Gallery.

I think my interest in art has been a lifelong thing, really. It was my parents that first forced me to study drawing as a child, since I didn’t want to do ballet or play the piano. But after I went to the United States for university I was free to study whatever I wanted, so I picked art history – something that I knew would make my parents mad. It turned out to be something I had a talent for and was able to get high marks without studying too hard.

Why did you decide to set up Banying?

During the pandemic when everyone was locked down, my friends and I were so bored and wondered what we could do. So I came up with the idea of holding an online salon talk and invited one artist, one art critic, and one writer – all experts in their field. About three to four hundred people came and we talked for four to five hours about so many things. Everyone just had so much to say! Women would ask questions like “how can I balance my role as a mother with being an artist?” — things like that. They all had so many questions for the three speakers. So following that talk I felt that women needed opportunities to discuss these kinds of issues and it seemed clear to me that many felt empowered by art, or could be. I contacted seven of the women I’d met while preparing for the online salon, some of whom were total strangers to me, and told them that I thought we could start an organization. They were all excited by the idea! I decided to call it Banying, which directly translates into “penumbra”, and we gave it an English name: In Light of Shadows.

What does Banying do?

Well, women’s arts festivals represent the core of what we do. As well as holding a large number of physical events we also stream them online, which helped us reach around 2 million people last year, with around 1,500 attending in person. Some of the art displayed is work we’ve commissioned, while other pieces are produced by us. It isn’t all traditional-style art displays; last year we staged a performance art production with 22 amateur performers. We’ve also held film screenings, a dance workshop and a number of talks. Last year we held 13 events at around seven different locations, so we manage to hold quite a range of stuff – and we’ve even attracted interest off some well-known foreign media like the Associated Press and Radio France Internationale.

What do you see as the main challenges for women in China?

For last year’s Women Arts Festival, I curated an exhibition based on 101 questions which were collected from teenage girls in rural China. After summarizing the 101 questions, I realized that their concerns could be grouped into three general issues: body shame, internal strength and intimate relationships. Body shame means that they try to fit into the “ideal beauty standard” shaped by social media and society at large; they’re ashamed of their body shape. Their questions are things like “how do I lose weight?”, “why do I look ugly?”. Intimate relationships focus on relationships with their parents, close friends, and boyfriends/girlfriends, and how often they feel lonely and disconnected. Internal strength is about how they feel they lack the confidence and power to be themselves, to pursue their dreams. These issues are not only experienced by women in rural areas, but also women in big cities. These main challenges for women in China go beyond age, economic status, and educational background. Of course, there are more urgent issues, like sexual harassment, domestic violence, and emotional manipulation. This is the reason why we hold art therapy courses.

How is Banying structured and funded?

Well we wanted it to be fairly formal when we set it up, but none of us had any entrepreneurial experience. Most of us had purely academic backgrounds but we put together a good business pitch and talked to a few investors. In the end we decided not to accept any money as we didn’t think we really had a sustainable business model.

In November 2020 we officially registered it as a company and it basically operates as a social enterprise. Currently we have two projects that bring in some income. One is the Women Arts Festival and the other is our art therapy courses. We’ve also had money off various individual donors we reached out to, as well as donations from a couple of foundations. I’m hoping we can maybe get some corporate funding in the future.

Can you tell our readers about the podcast you started?

We started a podcast called banying fm so that we could discuss topics related to women’s creativity in an accessible way. One of our most popular episodes talked about what art could bring to migrant workers, because art is often something that is thought of as if it’s in an ivory tower – far removed from people’s daily life. We talk about how everyone can enjoy art and how art can transform a person’s life, no matter what their social status. In that episode we discussed how the artist Can Fei had done a project with female factory workers in Foshan and how the project ended up inspiring one woman to change her life and become a successful entrepreneur. So far 346,000 people have listened online, which is a pretty good result.

How are the art therapy workshops organized?

Each of our workshops will have a maximum of 16 people and run for six to eight weeks. So it’s quite a long time for such a small group of people to be together. The people who attend are a really diverse bunch. There’s no typical person. We might get an unemployed woman from a village or a married professional that’s perhaps suffered domestic abuse. Many of the women have suffered sexual harassment, or perhaps even rape. And we might use theater to try and help them work through their experiences, with women staging a performance together. It’s all about allowing the women to start to externalize the traumatic experiences they have suffered. However, the first few weeks will just be about building trust within the group. We want each woman to trust that she can get healed and that she can get support from people within the group. And we want them to discover their power, that they have the power to deal with the difficulties in their lives, including the power to deal with trauma. For example, one girl who attended had been beaten by her ex-boyfriend and emotionally manipulated. In the class, she played the role of her ex-boyfriend and another student played her. They didn’t use a prepared dialogue; it was all spontaneous. The girl later said that for the first time in her life she had felt powerful.

Who teaches the therapy workshops and where do you hold them?

We have three teachers: one who specializes in tackling sexual harassment, one who specializes in domestic violence healing, and one who invented something called “ethnodrama therapy”— he doesn’t teach the courses directly but he does help to supervise. The workshops are mostly online as our students are from all over China, but our domestic violence specialist can also teach in person.

Banying has also worked with an organization called Bright and Beautiful hasn’t it?

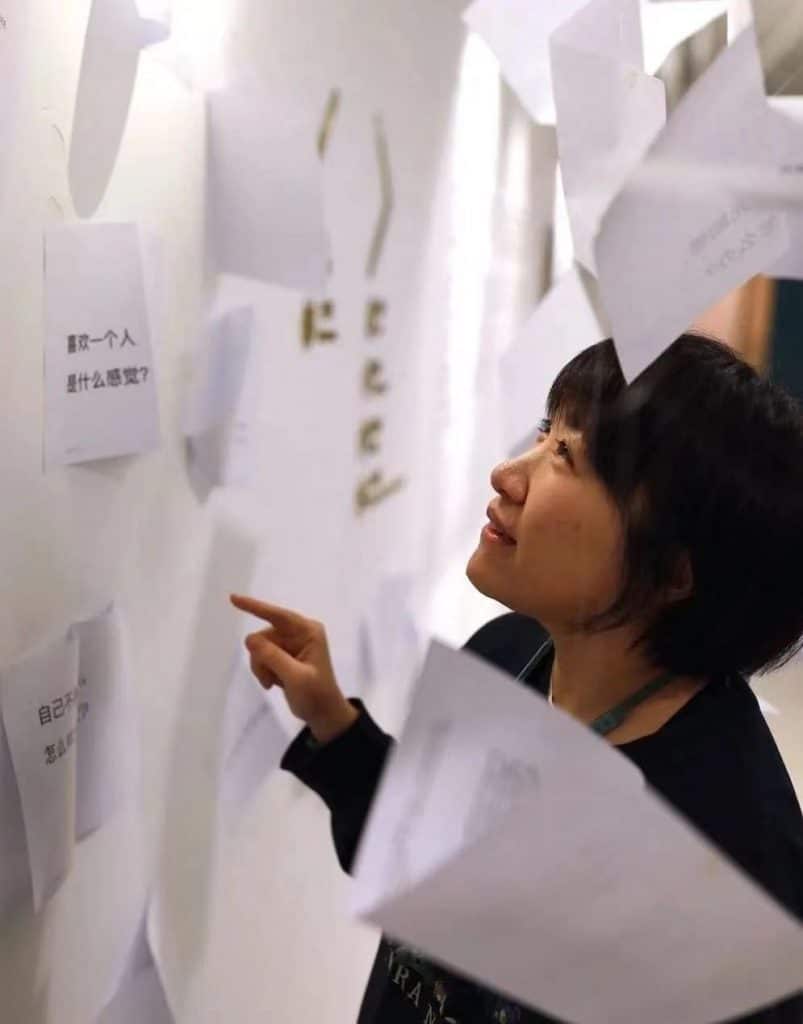

That’s right. Bright and Beautiful work with girls from villages in poorer parts of the country. These girls often have limited opportunities and are pressured to stay at home to support the family or to get married. But Bright and Beautiful encourages them to stay at school and to feel good about themselves and to feel that they deserve an education. They got in touch with us to ask for our help with an exhibition they were planning. They recorded questions the girls had about themselves, such as “what is love like?” and posted them to an online platform (Alipay) for members of the public to answer. We then collected those questions and answers and turned them into an exhibition, leaving extra space for visitors to write their own answers.

You’ve been involved in a lot of different things and have lived in both China and the United States. How have your own views evolved over time?

I would say the biggest change for me definitely occurred after I quit my job back in the United States. In China people have very high expectations for their children, parents want their kids to excel at school and university and then get married and get a great job. There seems to be a standard model that people feel obliged to follow. But I have come to realize that I don’t want that at all. I need to live my own life and people’s judgement is now no longer important to me at all. The most important thing is to do what my heart tells me to do. I learned to respect my inner voice. And everything seems to turn out in a better way; now I feel I have more confidence and energy to empower others.