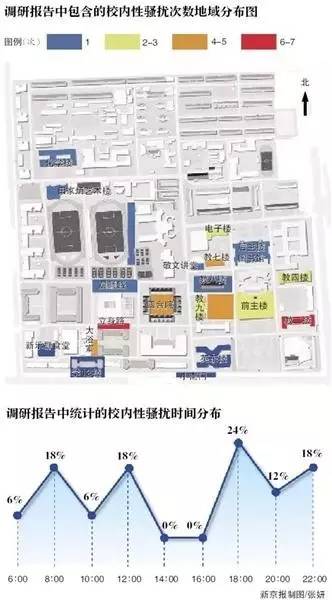

Part of the report illustrates an increasing rate in sexual harassment cases.

Beijing Normal University has released a report entitled “the Silence of the Iron Lion – Beijing Normal University’s Campus Sexual Harassment Survey”, which looks at 60 cases of sexual harassment over a ten-year span, analyzing their locations and times. The report highlights that cases of sexual harassment have been happening frequently over the past years, with many victims opting to stay silent. In releasing the report, the University hopes to reveal why people don’t say “no” to sexual harassment and encourage people to stand up to it. Meanwhile, the report also aims to analyze the power dynamics between the victims and perpetrators of sexual violence.

A graphic from the report reveals the most common times and places of sexual harassment.

The report’s release coincides with an increasing number of sexual harassment cases on Chinese campuses. In the beginning of 2016, there were various cases of female students at Beijing Forestry University being pulled by male strangers into the bushes on the side of the road. In the China University of Mining and Technology a man approached a group of girls at the campus gate pretending to ask for directions, but instead flashed them. In May last year, Zhejiang University’s Xixi Campus discovered there was a miniature camera hidden in a women’s bathroom in the library. Then in June, a female student at Capital Normal University received a Wechat message from her professor asking her to meet her at teahouse, where the professor proceeded to force her to kiss and hug him. Later than month, a female student at Nanjing University’s Xianlin campus awoke from an afternoon nap inside a campus building to find a seminal stain on her skirt. But even though campaigns against sexual assault have turned into a hot topic nationally there is still no clear legal definition of sexual assault, which makes practical management very difficult.

According to a report released by the University of California, sexual assault is defined as “unwanted sexual acts, sexual requests and other sex-related comments or body language.” It can happen between any members of a university, including professors, students and campus staff; and across or within seniority ranks. It also includes sexual bribes (to influence hiring, academic assessment, grading, professional ranks and projects) and malicious threats (including those that limit or interfere with one’s right to education, work or activities.)

The term “sexual harassment” originally appeared in American campuses in the 1970s, accompanied by the female rights movement. In 1975, professors at Cornell University decided to combine terms like “sexual intimidation”, “sexual oppression” and “workplace exploitation” into one term: “sexual harassment”. Public concern over cases of sexual harassment has had slower traction in China in the past, but has picked up in recent years.

In June of 2001, a female employee sued the company she worked for in Xian because her boss had sexually harassed her at work. She requested that her boss formally apologize to her and provide compensation. This was China’s first case of litigation over sexual harassment.

Then in 2005, the “Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Women” was passed, enabling victims of sexual harassment to protect their rights with more ease. This was the first law in China aimed at curbing this problem. It did not however set strict guidelines on the scope of sexual harassment. A similar law was implemented in 2014 aimed at curbing sexual harassment on campuses, especially those that involve teachers who demand sexual bribes from students, but the law failed to clarify the meaning of “improper relations between students and teachers.”

Due to obscurities in the laws, difficulties in obtaining evidence when investigating harassment cases, and victims’ unwillingness to speak out because of embarrassment, uncovering cases of sexual harassment remains very difficult. In addition, some universities cover up instances of harassment on their campuses in order to save their reputation, hoping that the victims will slowly forget about it or keep quiet.

Beijing Normal University nonetheless hopes that the release of their report on sexual harassment can help create safer work and study environments, while at the same time encouraging people to stand up and say “no” to harassment.