In 2022 and again in the fall-winter of 2024, Poyang Lake—China’s largest freshwater lake—was struck by extreme drought, with water levels falling below historic lows. These unusual dry spells drew renewed national attention. In response, Liang Zhetao and his team embarked on a journey along the Yangtze River, investigating the ecological impact of extreme weather on Poyang Lake and documenting how local communities perceive and adapt to climate change. Their goal: to write a “Poyang Lake Climate Revelation” that captures the lake’s present and imagined future through the lens of wildlife and village life.

Born and raised in Guangzhou, Liang grew up immersed in the region’s subtropical ecosystems. Early on, he cultivated a keen eye for environmental change, leading his school’s biology club and joining butterfly expert Chen Xichang in nature monitoring and public education. Though he later studied law, his interest in ecology persisted. Interning with Friends of Nature introduced him to environmental policy, and he continued initiating cross-disciplinary research, including a project on the Xijiang River, where he examined the effects of hydropower on aquatic life and fishing communities.

In 2022, after reviewing the Environmental Impact Assessment for the Poyang Lake Hydraulic Project alongside media reports on drought, Liang become skeptical. The report suggested that infrastructure could “save” the lake from climate impacts, but its ecological conclusions felt vague. He submitted a critical public comment and brought his concerns to the Linglong Initiative, a climate-focused fellowship.

Initially planning a project on butterfly science communication, Liang shifted focus after mentors encouraged him to address Poyang Lake and hydropower more directly. Drawing on prior research and incorporating a climate angle, he submitted a new proposal and secured funding. His project would investigate how drought affects local wildlife—such as finless porpoises, mussels, and migratory birds—as well as the lake’s human residents.

In early 2023, Liang joined a porpoise protection expedition to Poyang Lake. He was struck by the harsh reality of drought: kilometers of cracked lakebed, dead mussels, and dried grass told a story that no report could fully convey. Climate change, once abstract, became tangible. Minor drops in water levels drastically altered habitats, jeopardizing biodiversity and livelihoods.

This realization led Liang to focus his project on “climate perception”. He studied not only ecological indicators but also how local people experience and interpret climate change. Poyang Lake’s dramatic seasonal shifts made it an ideal case study. To bridge gap between urban concern and local experience, Liang published his findings on his science blog “Nature Folding” and recruited a research team to join him in fieldwork at the lake.

The team revisited Kangshan, a critical porpoise habitat. Despite stable porpoise numbers, patrol members reported rising threats: lower water levels caused porpoises to be stranded or trapped, with food becoming harder to access. Patrols intensified, but concerns remained: “Who knows what next year will bring?”

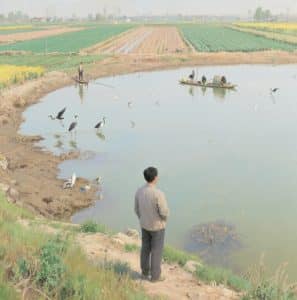

Liang also investigated the “migratory bird canteens”—farmlands set aside to feed birds during droughts. Though effective, when food was depleted, birds relied entirely on purchased grain. Is this sustainable? Is it ethical?

He explored the complex dynamics of dish-shaped lakes, formed during dry seasons and contested between fishers and birds. Once managed through community agreements, these areas now lack regulation after the Yangtze River fishing ban. Liang sees potential for collaborative water-level management to support both conservation and climate resilience.

Meanwhile, Liang returned to the Xijiang River to explore how climate change and hydropower intersect. Interviews with fishers revealed unique local knowledge: floods, typically seen as disasters, could mean fertile fishing seasons.

Amid the uncertainty of his journey, the Linglong community became Liang Zhetao’s source of strength. He cherished every exchange with mentors and peers. At a gathering, mentor Chen Dan articulated what Liang felt: “As long as you’re on the path of discovering problems, there’s no need for anxiety. Identifying and presenting problems is meaningful in itself.”

“I completely agree,” Liang said with a smile.